Germany

Berlin: A Strange Mix

Berlin is a weird place. It is a strange mix of grunge, piercings, drugs, and progressivism with order, organization, and a history of fascism and completely intrusive regimes. Most of what we encountered here, too, was a sort of Frankenstein experience. To be fair, we weren’t in Berlin long enough to offer a solid assessment. One of the great tragedies of doing a world tour in 3 ½ months is that you can’t see all that much of the world in that time, let alone see it well.

I should have just turned our Dutch rental car in at Berlin. I would have liked to have kept it until we got to Bulgaria or Turkey, but Avis said we could only drive it in Western Europe. I could have turned it in at Berlin and avoided backtracking from Luxembourg to Amsterdam only to catch a train to Berlin. We got to Berlin, though, early enough in the afternoon to see a couple of sights on the way to our second hostel stay. We hopped off the bus and made our way toward the A&O, a huge chain hostel, with several locations in Berlin.

The train station was right near the Reichstag building and the Brandenburg Gate, so we walked to both of those. We could barely squeeze through the crowds or get a good picture of the Brandenburg Gate, because of the massive press of people in Berlin for EuroCup 2024, a huge soccer tournament. They were playing right in the shadow of the gate. The place was overrun with Croatian and Spanish football fans lining up and drinking in anticipation of their 15:00 kickoff. By far, the Croatians outnumbered the Spaniards. That didn’t help much in the game. The Croats surrendered three goals in the first half. The fans were crying in their beers at the hostel that night while a lone Italian basked in his country’s win over Albania in the nightcap. Eurocup explained the high cost of our Berlin room.

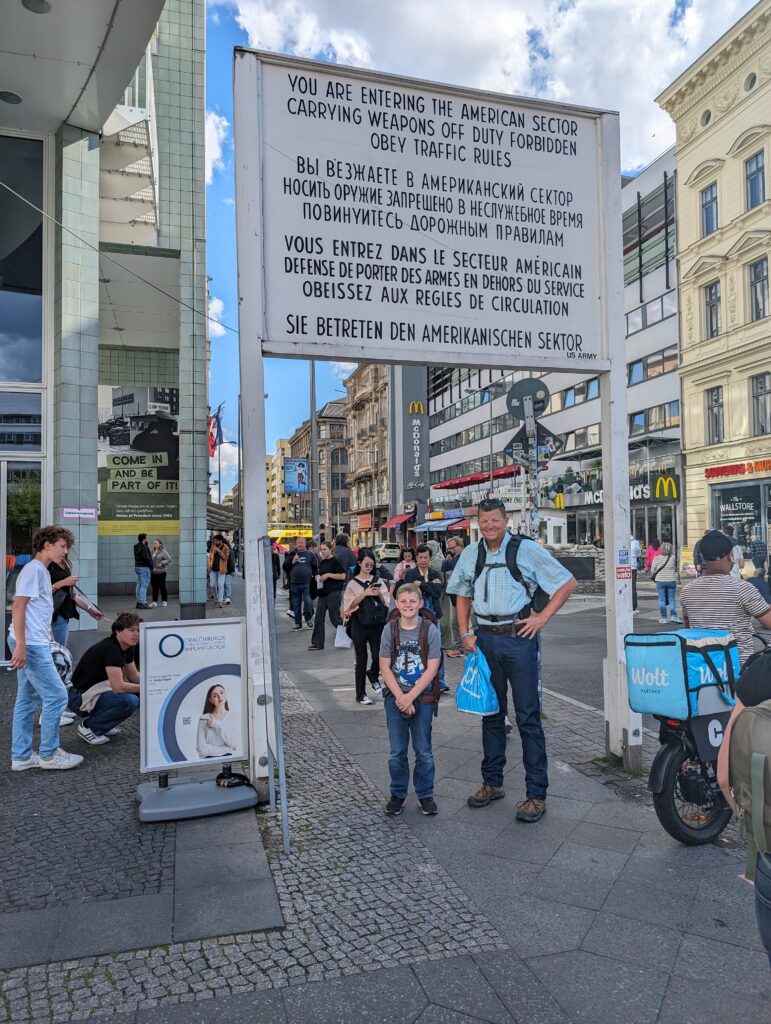

We made a quick stop at Checkpoint Charlie, the famous entry into the American sector of Berlin. There is only a small white building and a sign here, so we didn’t stay long. Caleb was pooped from toting his backpack even though we had only been a mile or two. We had a seat and enjoyed a pastry while I waited for Caleb to recharge. Caleb didn’t recharge. I had mercy on him and hired an Uber to haul us to the hostel. That allowed him to rest a bit more. After check in, we shed our big packs, after which Caleb was game to walk around a bit more.

We headed out for dinner. I wanted to try some traditional German dishes, but the first two places we tried were closed, perhaps due to the football tournament. We did eventually track down an open spot. I tried a Hungarian fish soup appetizer, which was good. I had a veal schnitzel with fried potatoes. I liked this better than Caleb’s curry wurst, which was just OK. We managed a better night’s sleep, but still had partying 20-somethings turning the lights on at 1:30 and 3:30, for some unexplained reason. It was light early, so I hit the road to run before church.

I did find a Church of Christ in Berlin, but it was an hour voyage via the metro. This congregation was established by American missionaries in the 1950s. There were seventeen in attendance. Andreas, who led the service, almost apologetically explained that the service would be in German.

“We are trying to reach our local neighborhood, which requires us to use German,” he said with some trepidation.

“I wouldn’t expect a service in Germany to be in a language other than German,” I tried to reassuringly offer.

“Not everyone who visits feels that way,” he said with some relief.

The small crowd reinforced my aforementioned observation that Europe is mostly a post-Christian society. I passed several empty denominational buildings en route. Most of us were visiting Americans. We enjoyed a nice, participatory service. The songs were in German. They were mostly contemporary German Christian hymns, not retread 19th century hymns with translated lyrics that help you sing them without speaking the language as we often see in Latin America. It was potluck day, and we were invited to stay and share, which we did. The fellowship was good, and I collected several interesting stories.

Raymond was visiting from California. He works in Salinas with convicts, trying to share the gospel with them. Every year, he takes a four week sabbatical to Germany where he teaches and writes to recharge. We shared some discussions on the state of Christianity in Europe and the world, as well as the regrettable situation in most of our Church of Christ Universities. Andreas is a retired police officer from Berlin married to the daughter of a former American missionary. I so enjoyed hearing him share his accounts of the demise of the partitioned Germany and the fall of the Berlin Wall. He got emotional explaining what the event meant to him personally. He said that it was something he had looked forward to his entire life, but never believed would actually happen. Other than perhaps his wedding day, the fall of the Berlin Wall had been the most meaningful, emotional day of his life. His eyes got misty telling the story. This really set the stage for seeing the Stasi Museum and the Berlin Wall Memorial later that afternoon. (Continued)

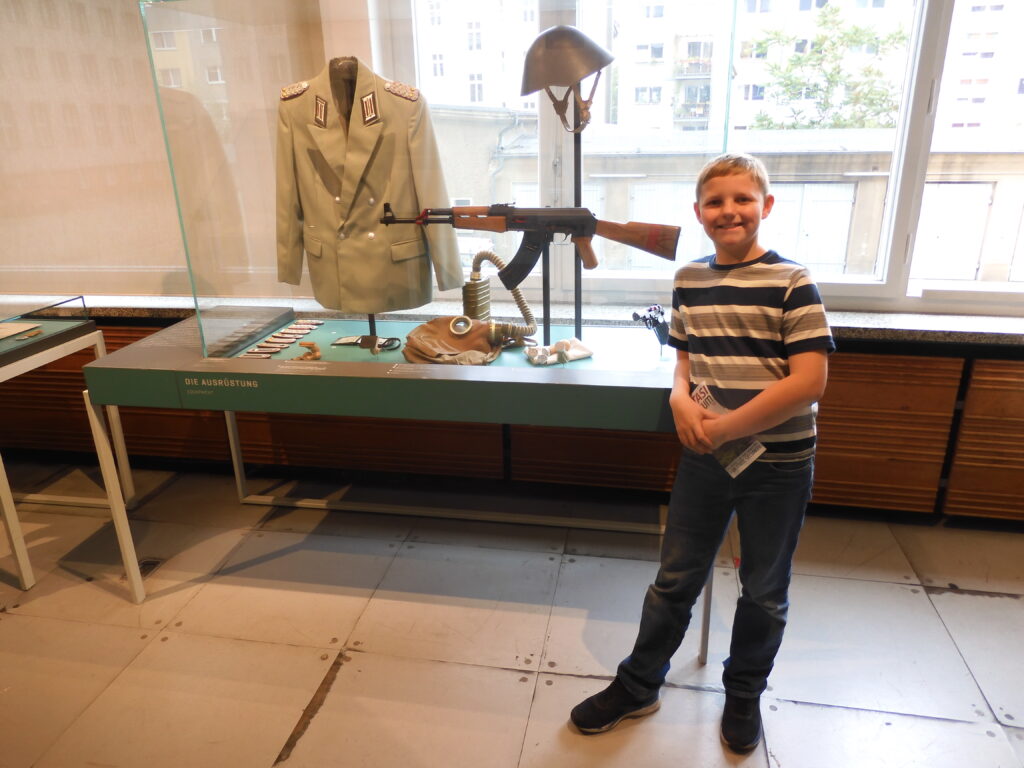

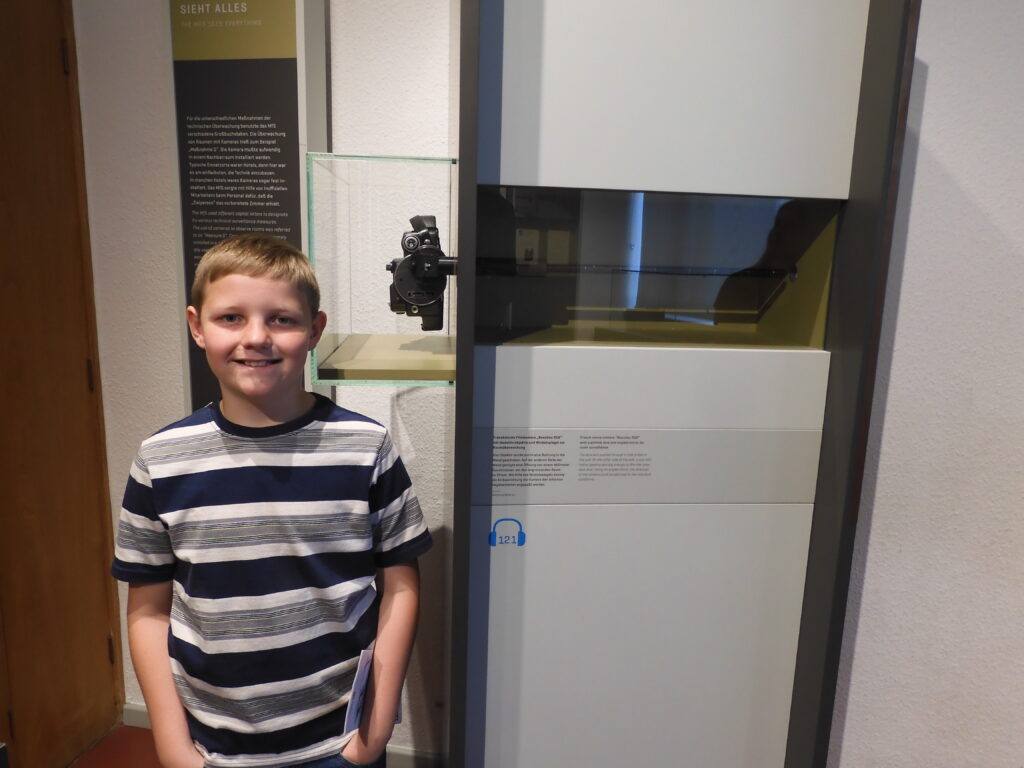

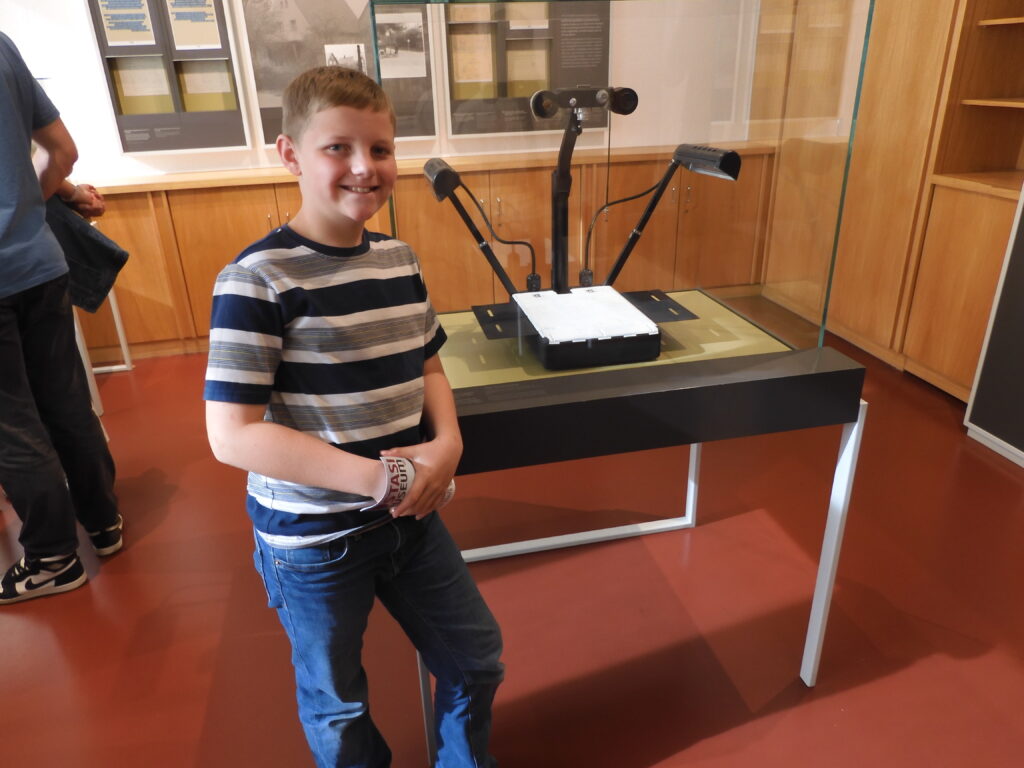

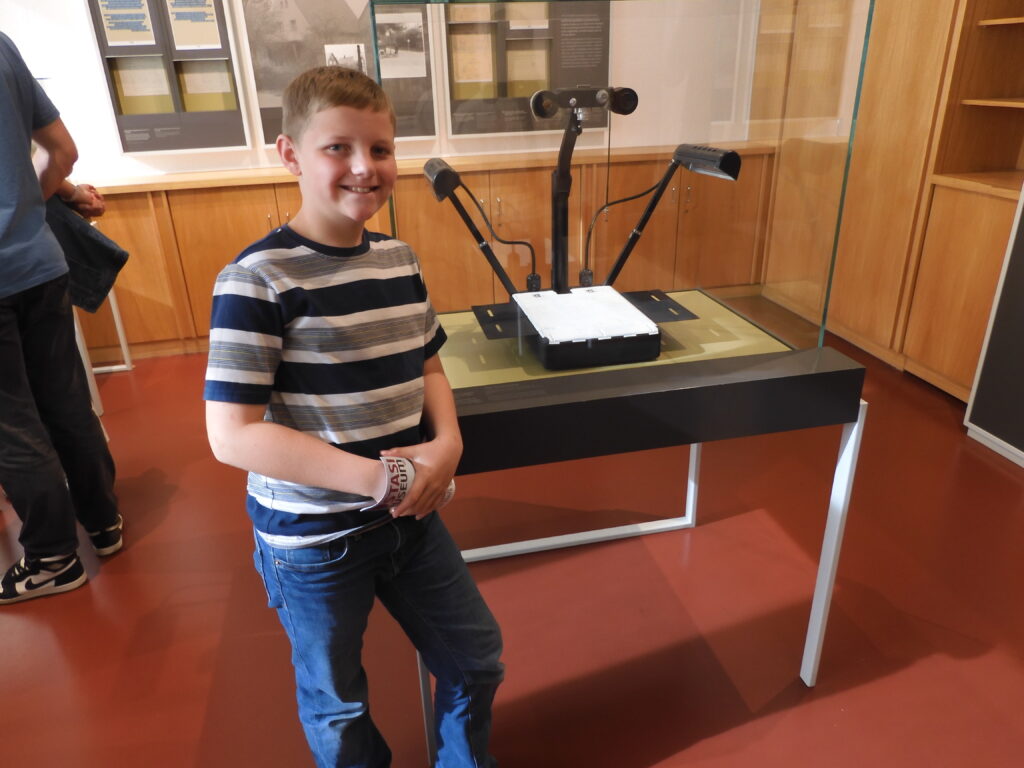

We traded off some sightseeing time for fellowship. It was about 14:30 by the time we headed back toward the metro station to make our way to the Stasi Museum. Several observers recommended a visit of 1:30 at this stop. You already know what that means to me… I thought we would be OK getting there with 2:30 left before closing. We saw most of it, be we were herded out not having seen a couple of the last rooms.

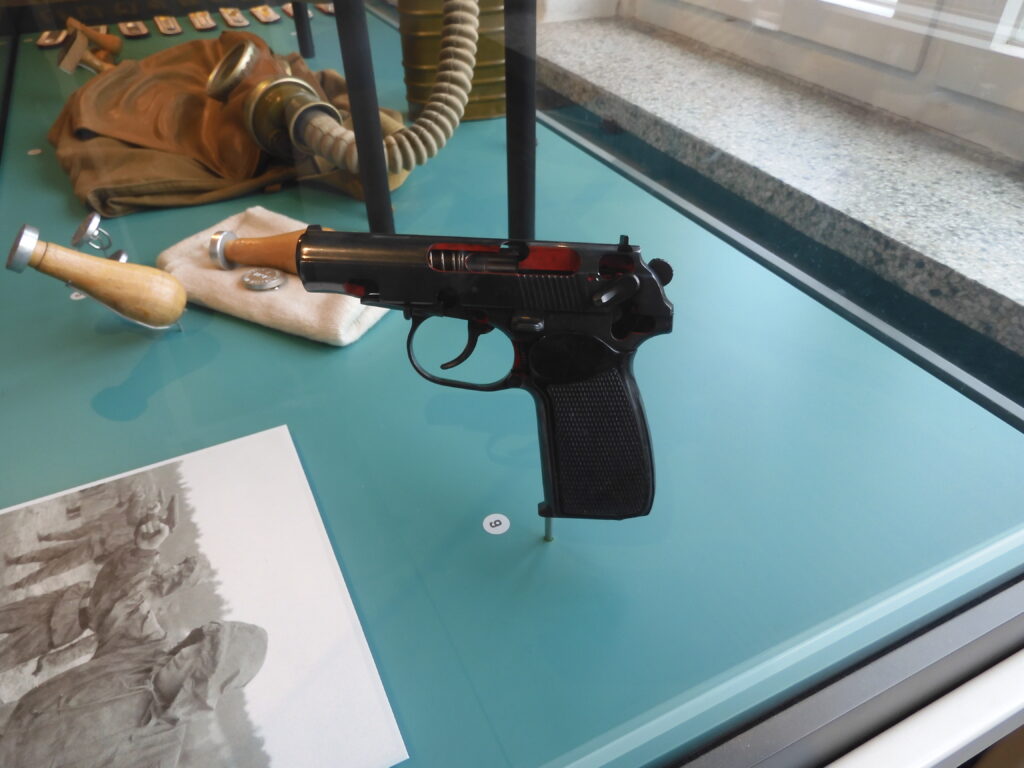

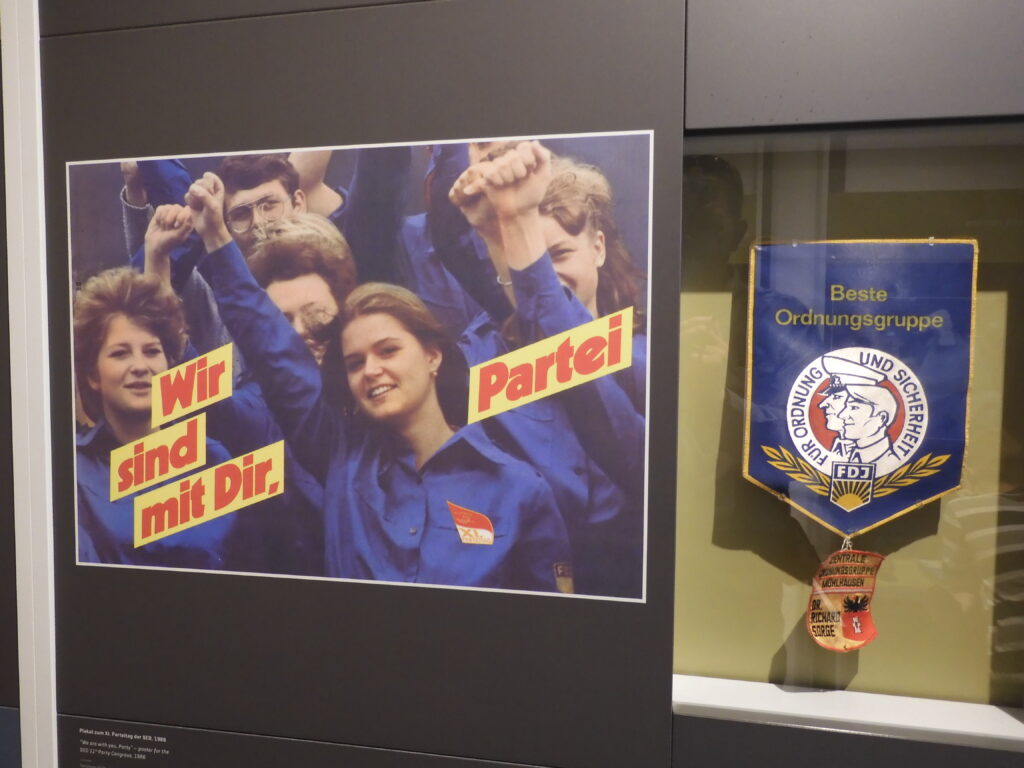

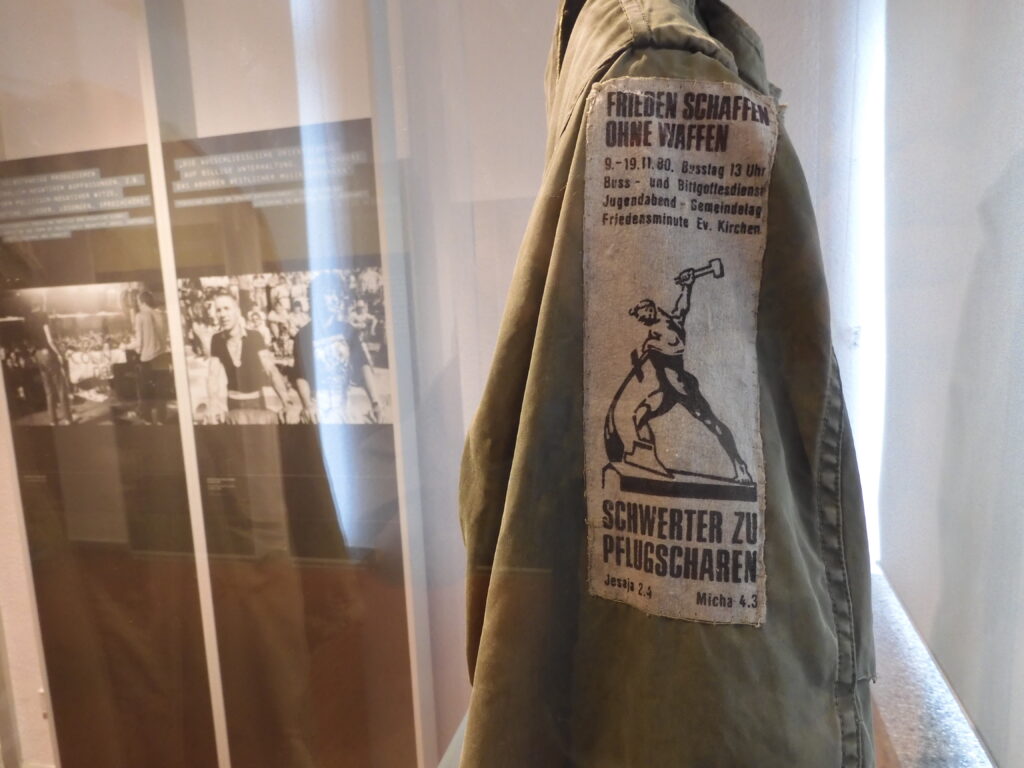

The Stasi Museum is dedicated to the East German Secret Police. Stasi is a colloquial term for Ministerium fur Staatssicherheit, Ministry for State Security, abbreviated MfS. After World War II, Germany was occupied by the four major conquering allied powers, the US, the UK, France, and the Soviet Union. Sectors of control were allocated to these occupation forces in both Germany as a whole, and the city of Berlin separately. After Germany could stand on its own, France, Britain, and America ceded control of their zones to the Federal Republic of Germany (known as West Germany). The Soviets installed a puppet state in East Germany called the German Democratic Republic. The GDR was a one party state, administered by the East German Communist Party (the SED). The MfS operated from 1950-1990, keeping files on over 5.6 million people. They were completely controlled by the SED, and operated entirely as an instrument thereof. In the early years of the MfS, they often used overt violence to enforce communist control of the East Germany. As time went on, this was less possible, and for public relations’ sake, they resorted to spying and psychologically coercive tactics.

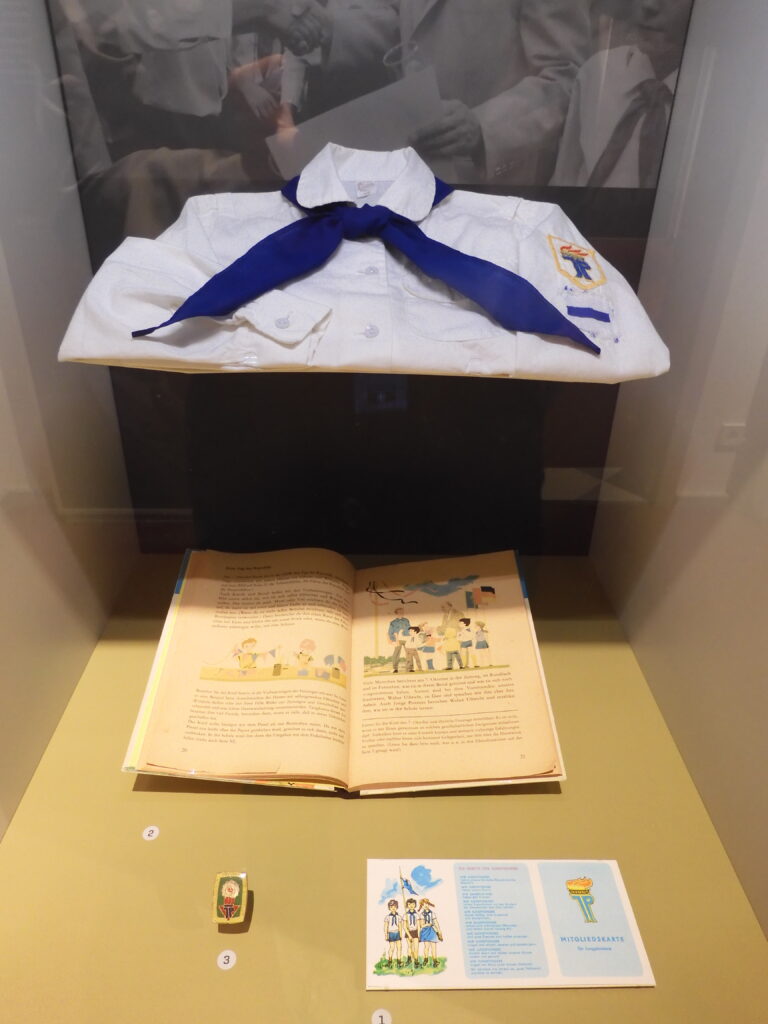

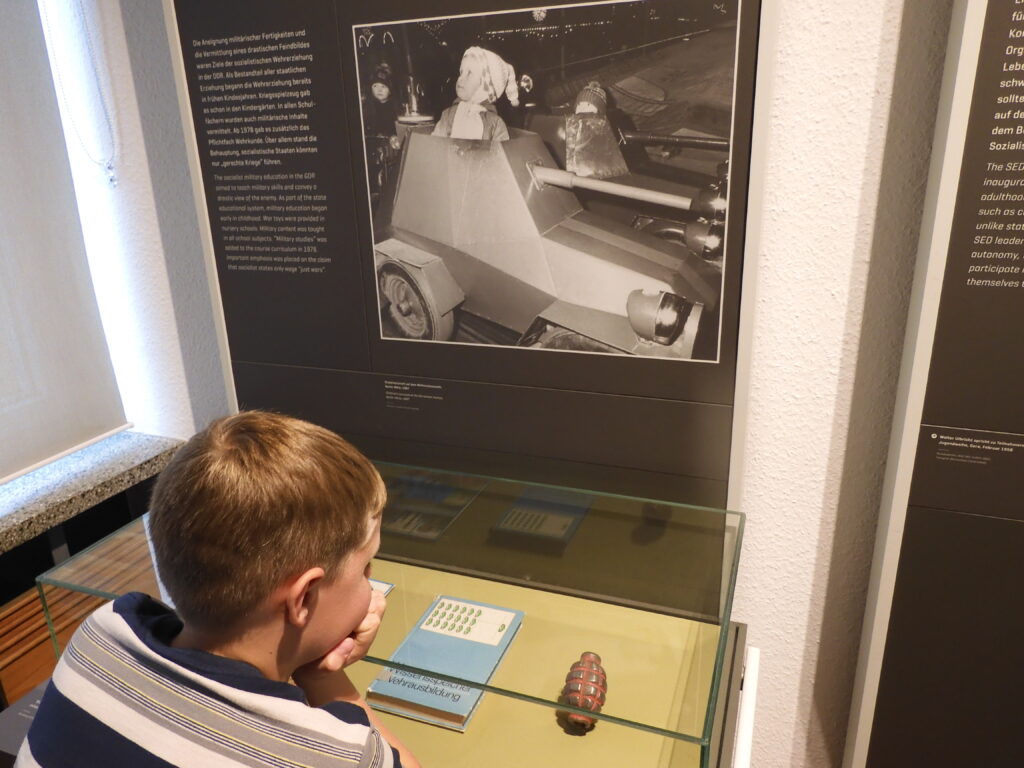

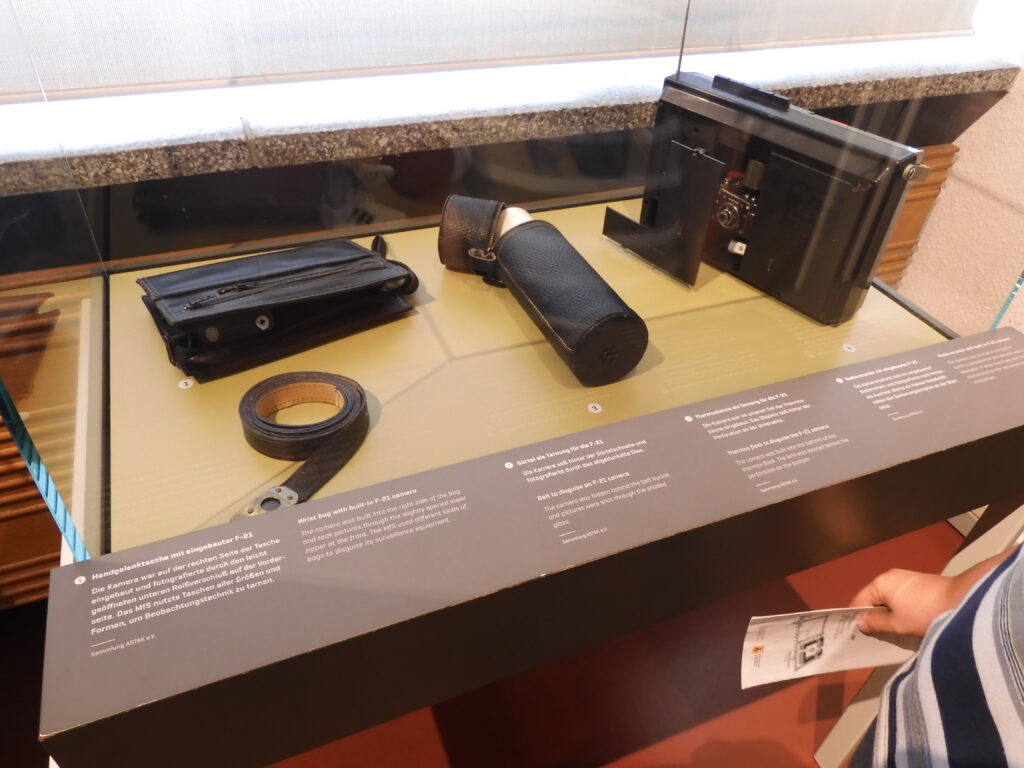

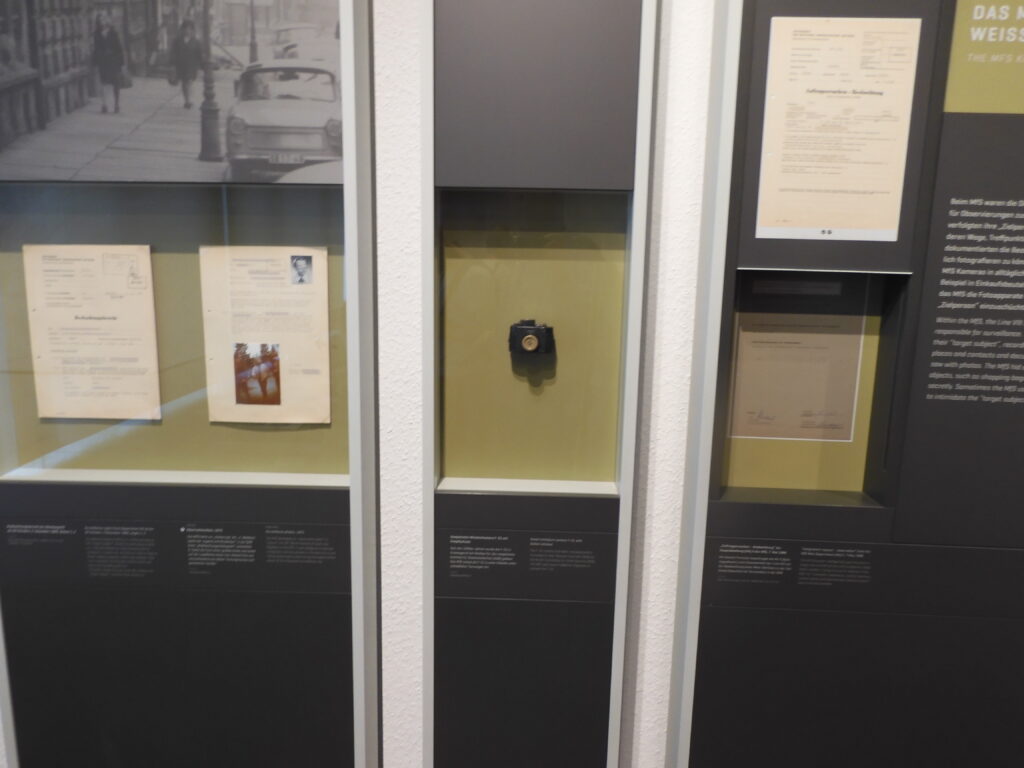

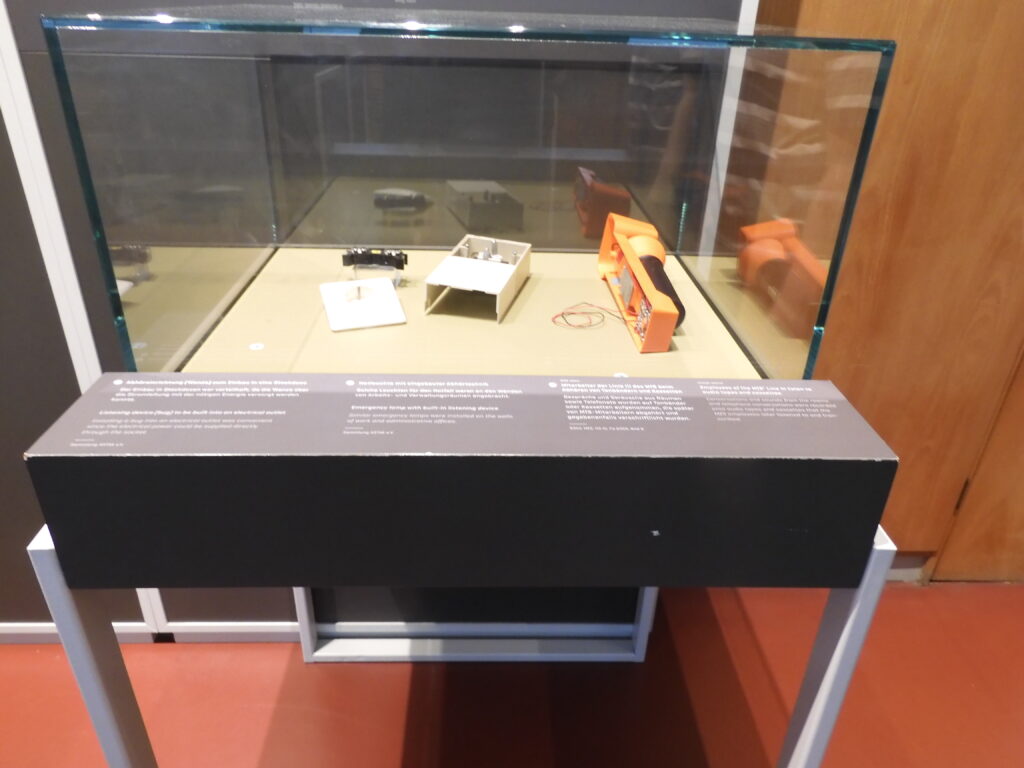

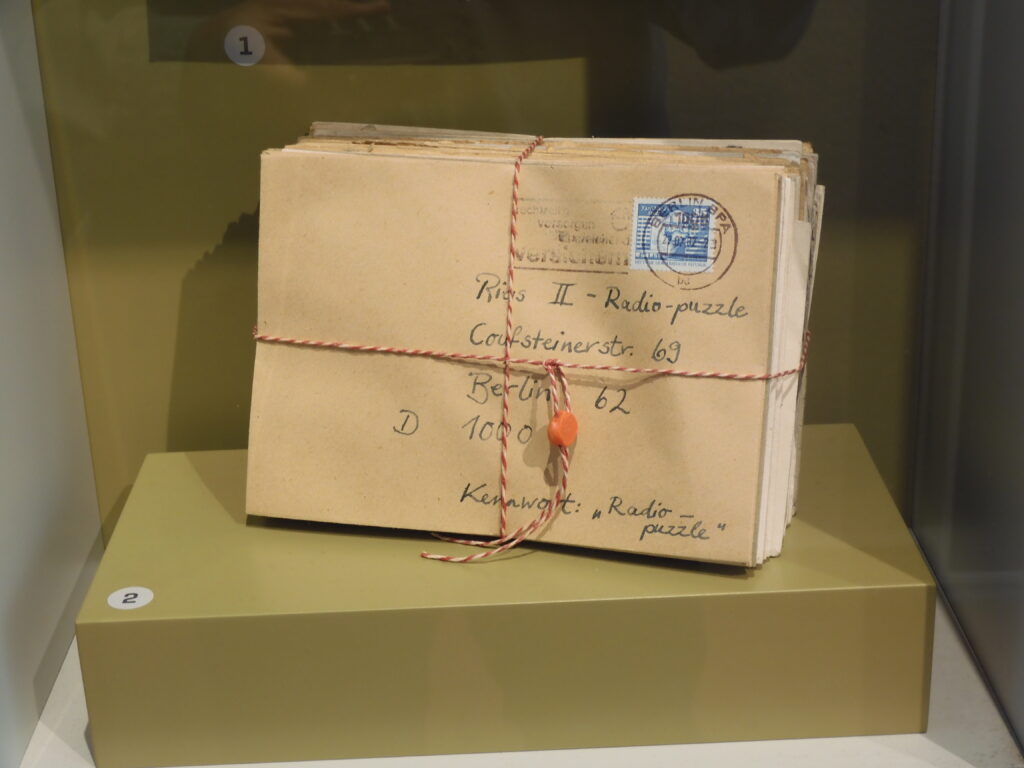

In many ways, the Stasi Museum was sickly comical. Much of their modus operendi seemed so ridiculous as to be only marginally credible. You wouldn’t believe some of the tactics if they were part of a fictional spy novel or Bond film. They had agents everywhere. In a country as small as East Germany, they employed over 90,000 agents. They utilized a network of unofficial informants totaling another 180,000. They steamed open letters, and ironed them back shut. They had a device to obscure post marks, so held mail would not be suspected as having been searched when it arrived late (because the bureaucracy took too long to inspect it). They surreptitiously copied keys and searched peoples’ houses. They installed bugs and cameras in houses and motel rooms. They had special cameras that could be installed anywhere for surveillance – even in a belt buckle or water jug. They created fake stories to discredit people they saw as political opponents. They really wanted to know everything about everyone. They had athletes who monitored other East German athletes competing internationally. They even had a file of collected odors they could use to verify the authorship of certain documents. They had indoctrination guidelines for every level of education, complete with curriculum and “commandments,” which ranked loyalty to the state above obeying your parents!

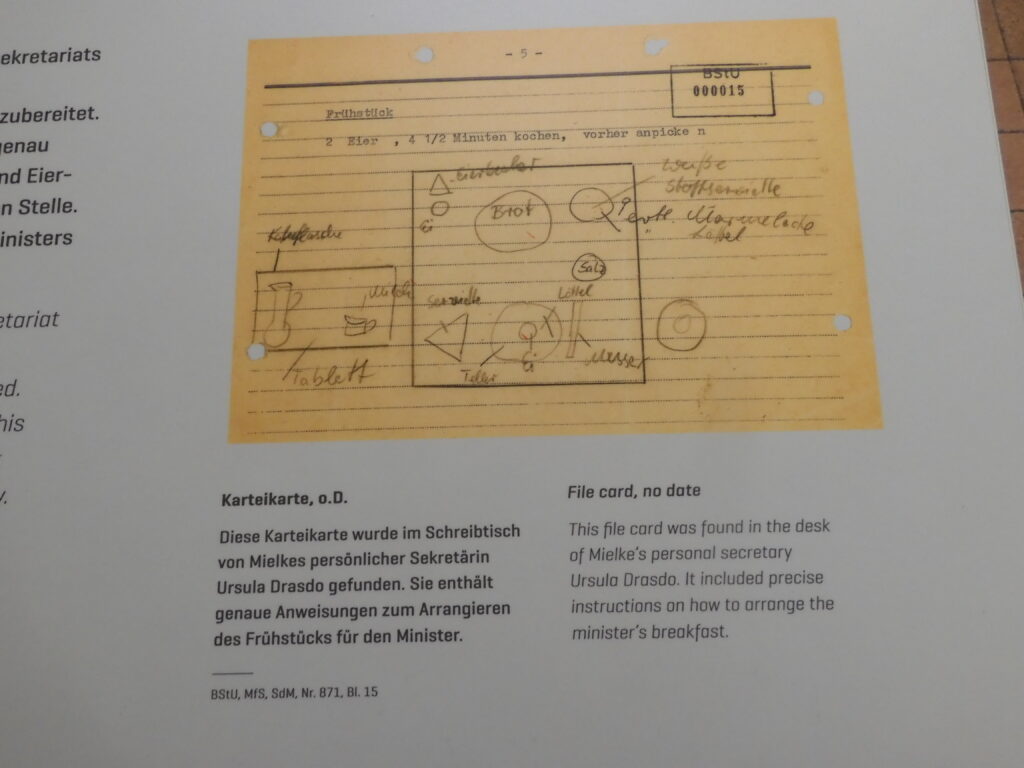

It took people with peculiar personalities to run such an organization. Erich Mielke, who was director for quite some time, was the star Stasi villain in the museum. Many of his quirks and directives are documented as you make your way around the facility. There was a small kitchen on the floor where his office was. One display shows hand written directions for how his breakfast was to be served. He had exact orders for how many minutes his eggs were to be cooked, how many times the yolk was to be punctured, and a hand written diagram of how the table settings and foods should be laid out. As I was looking at this ridiculous exhibition of micromanagement, I noticed a middle aged woman with a short haircut smirking as she photographed the breakfast diagram. She explained to me in broken English that she was a law enforcement employee from Southern Germany. She had been assigned to the staff of a police chief in charge of security for the Euro Cup. She apparently received just such a diagram from her boss, with his breakfast instructions. She was sharing that with her fellow employees, with special care not to place the photo in the wrong texting group. “Be careful, he may have agents everywhere,” I jokingly warned as we shared a good laugh.

The peculiar covering over the Stasi building’s entry (shown in the picture) was crafted after high rise apartment buildings were erected from which residents might be able to see into front entry. As communist paranoia increased, neighborhood buildings and whole city blocks near the Stasi headquarters were leveled once they were perceived as security threats. The residents were forcibly moved, as were those with homes destroyed by construction or expansion of the Berlin Wall. On East German maps, the entire area around the Stasi complex was depicted as a blank white blob. Of all the silliness and intrusiveness on display, however, the thing that struck me most was the level of detail in the files they had collected and stored. In a pre-internet age, they had recorded how many untrustworthy people were on each block, how they knew this, who had collected the information, and what the cover story was of the person who had collected it in case the person needed to be approached again with the same lie in order to gain more information about a neighbor, friend or other activity. (Continued)

Once our time ran out at the Stasi Museum, we took the subway to the Berlin Wall Memorial. In the year leading up to the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, over 200,000 immigrants fled to the West through West Berlin. This was both a socioeconomic and a public relations disaster for East Germany, the old Eastern Block puppet states, and indirectly for the Soviet Union. In order to prevent people from leaving, the GDR came out one night and began construction of a 155 kilometer fence completely surrounding West Berlin, which was an island inside communist East Germany. Over time, this boundary was seen as inadequate. It was improved and eventually consisted of a smaller inner wall and a larger outer wall with a sort of no man’s land in between. The empty space had guard houses about every 250 meters.

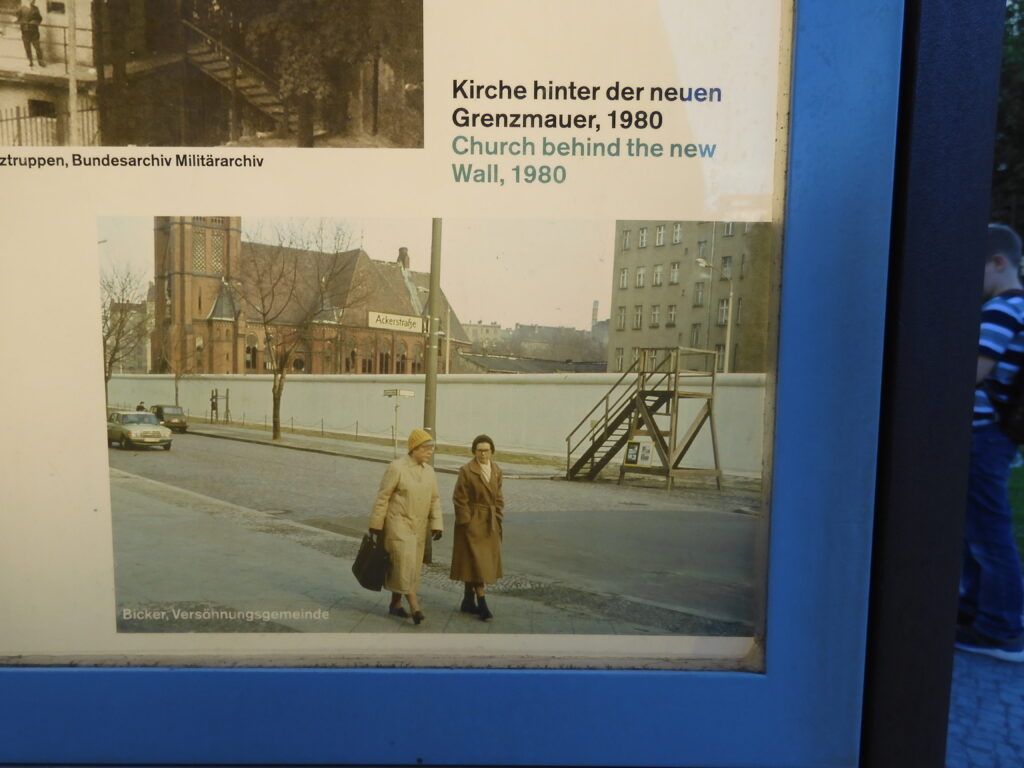

The wall came down in 1989 as communism collapsed in the Soviet Union and its satellite states. Protesters chipped pieces out of the wall and destroyed much of it, and the guard towers. In a few places, sections have been preserved for remembrance and public knowledge. Quite a bit of the wall area around the memorial consists of only the structural bars, which can be passed through readily. In this sector, there are larger sections of the old inner wall visible. In a few places, the walls of buildings served as the boundary. In them, windows had to be bricked up. There are accounts of refugees jumping out of upper floor windows into the rescue equipment of West Berlin fire brigades. In the park around the memorial, they have a rebuilt guard tower. They have marked several places where people had tunneled under the wall. In one place, the SED had blown up a church – coincidentally named the “Reconciliation Church” – because it stood right in the path of the wall, testifying to the injustice of the entire regime. A chapel has been placed on the site, but appears to be little used for any religious purpose now.

Surprisingly, only 180-some people were killed trying to cross the wall or were otherwise incidental casualties to communist enforcement of this zone. A marker lists their names and displays photos. We walked this entire length of wall, and listened to several of the presentations before heading back to the hostel. We decided to just eat our groceries for supper so Caleb could get in bed a bit earlier. He was ready for bed when we were done, and asleep by 9:00.

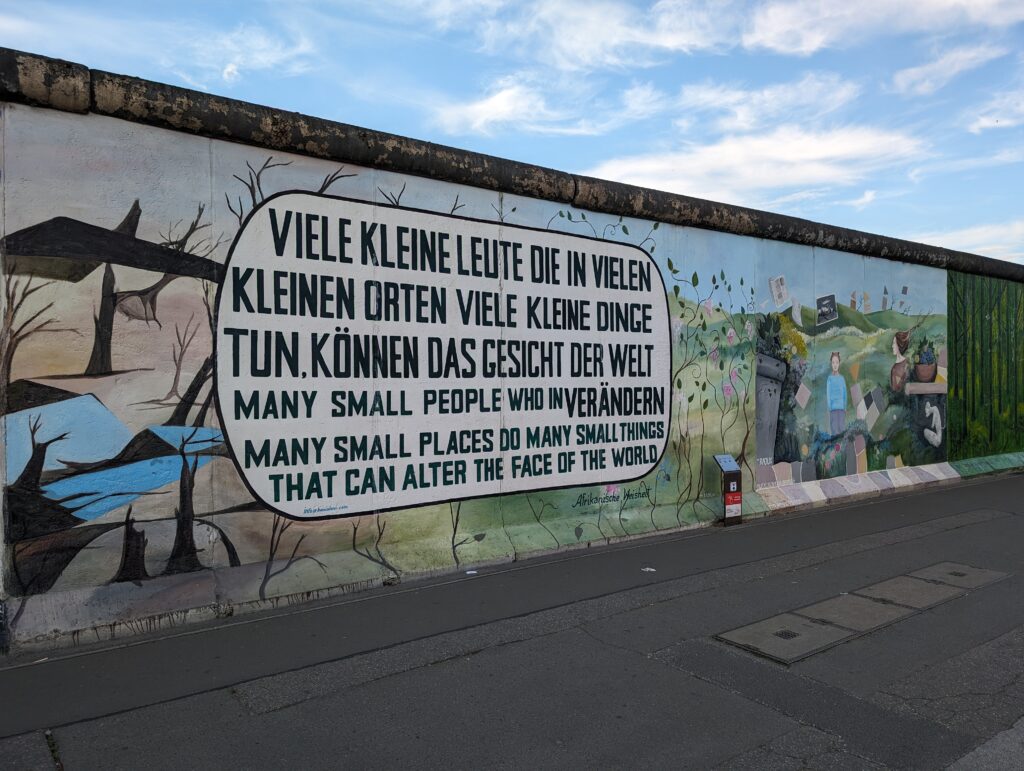

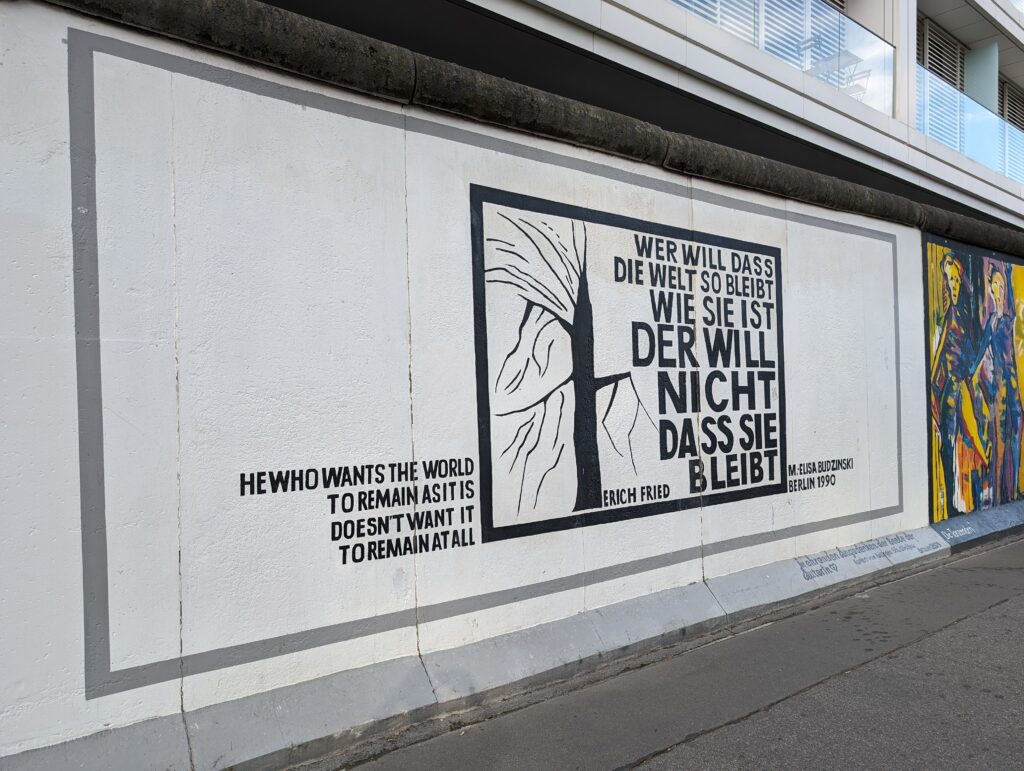

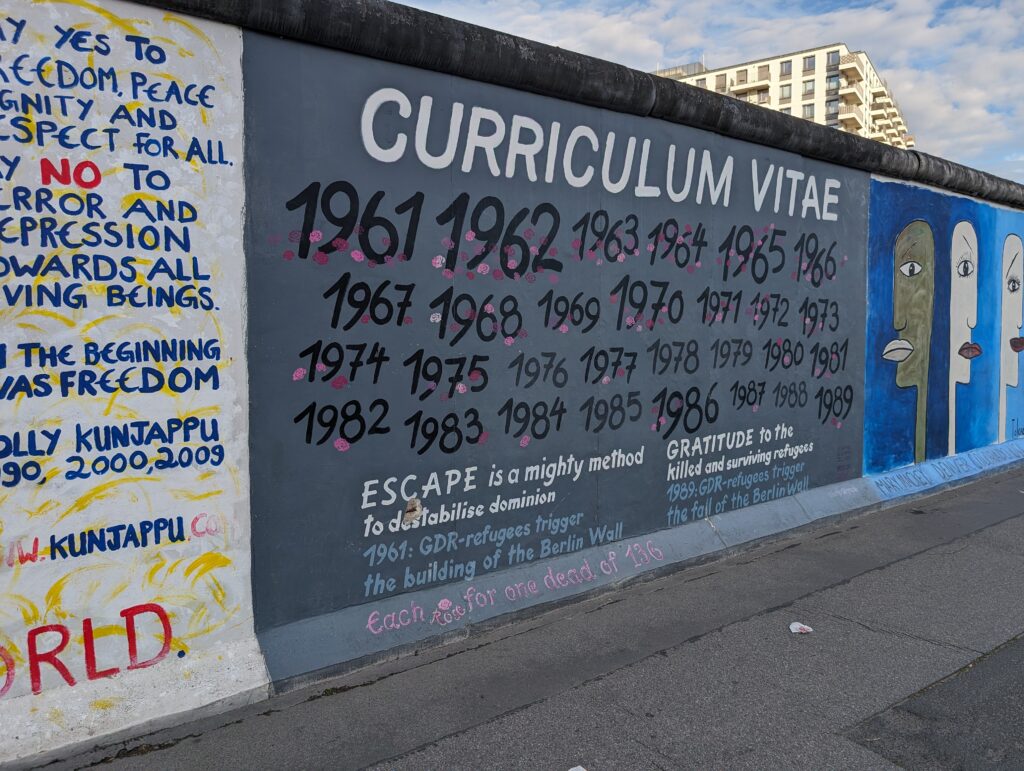

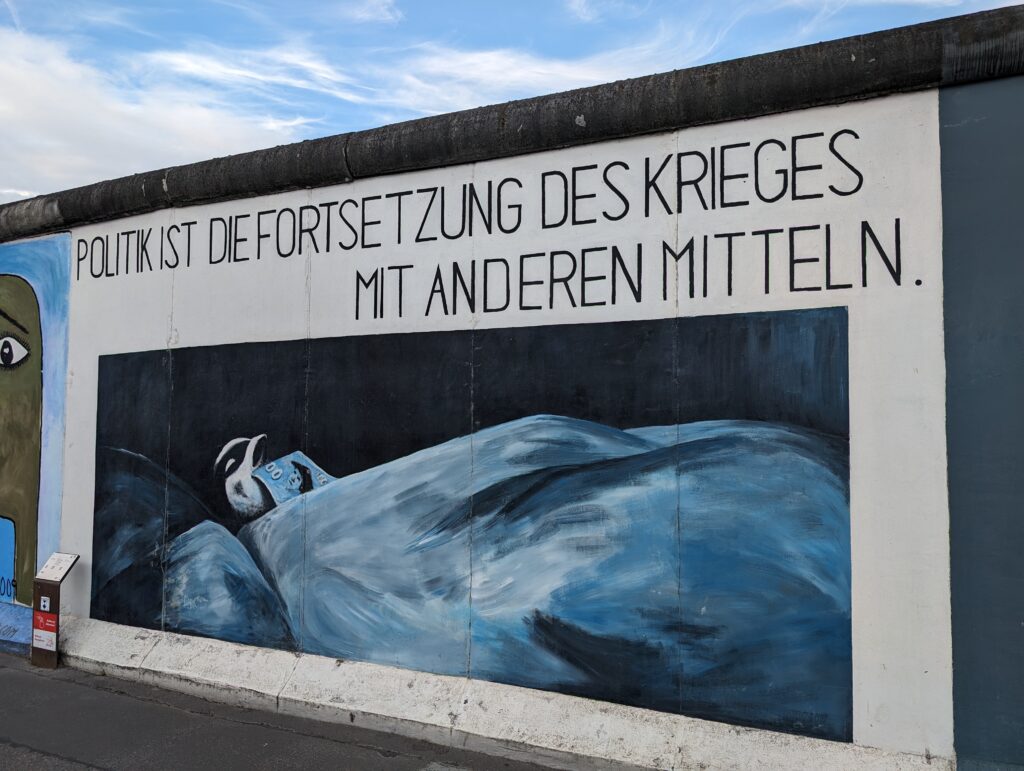

I arose early. There was one more thing I wanted to see. The East Side Gallery is another long stretch of Berlin Wall that remains intact, and it was less than a mile from the hostel. In an odd, sort of Frankenstein presentation, artists were summoned to create murals on wall’s remains. They were marked out in precise, organized sections. Artists were invited to place graffiti on the wall. Some of the art looks like cartoonish or unprofessional graffiti, but a lot of it was done by art students and professional artists looking to strengthen their resumes with a very public display of their work. This whole area is set up as a walking tour, a combination modern art/political art/graffiti art exhibition. There are descriptions you can download of each piece. There is a museum explaining all of it. The place is sort of publicized as an ad hoc display of street art, when in reality it was an organized, by invitation only affair. Nevertheless, it is quite interesting. Much of it offers political commentary, or at least an expression of the artist’s thoughts, hopes and fears for life after reunification and the fall of the Soviet communist governments. I have included photos of several of works I found interesting.

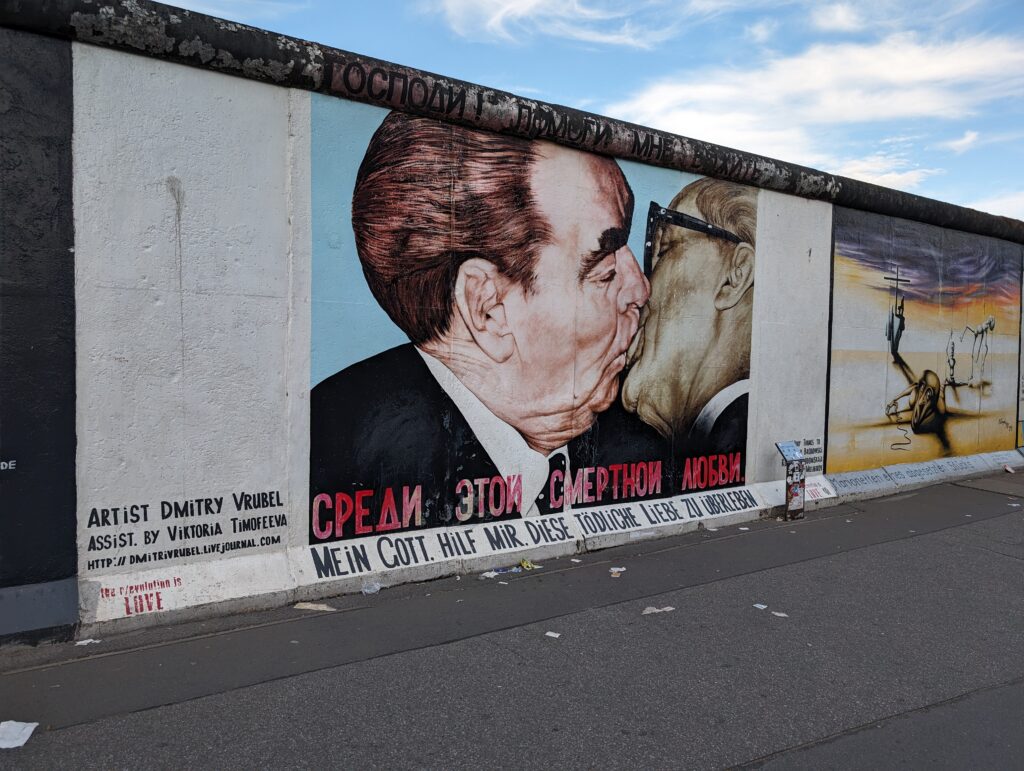

Perhaps the most famous work on this section of wall is the “kiss.” It is a painted recreation of a mouth kiss between Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and East German Chairman of the State Council Erich Honecker. It is entitled something like, “Thank God I Survived This Deadly Kiss,” referring to the artist outliving the strange, pseudo-loving, cringe worthy relationship between the Soviet Union and East Germany, pretty much expressed just like this really weird, sick looking kiss. These fraternal man-to-man kisses were a strange feature of Soviet culture to those of us in the West who observed the tradition. The 1979 kiss in the photo was not a one off thing. Google “Soviet kiss,” and you’ll find many examples once you get past all of the pictures of this mural.

There is a lot of weirdness to the art on the wall, but I will comment here on just one more aspect. There are several empty spaces where a mural is supposed to be. The original art dates back to 1990. In the early 2000s, the masonry on the wall needed to be restored in order to preserve it for the long term. That obviously could not be done without disturbing the murals. The original artists were contacted asking them to come repaint their works after the restoration was complete. With stereotypical eccentricity, several of the artists squabbled, quibbled, or balked about their art being disturbed. Most returned and repainted their works. Some repainted their works with a signature that passive aggressively complained about having to redo it. Others refused altogether. This last group accounts for the blank spots. The placards explaining the art just say what the piece was, and that it no longer exists. Those stretches of the wall are just the original off white color.

I witnessed this Frankenstein art display as part of my own Frankenstein exercise activity. I needed to run, but wanted to see the East Side Gallery. It was only one kilometer away. I ran to it, going the long way around the river and over a bridge on the far side. I slowed to a walk to traverse the ¾ mile long section of painted walls, and then ran the 1 km back to the hostel in time to shower before waking Caleb up so we could get to our train on time.

We both got ready, packed everything, and headed down to eat a bowl of cereal before hoping on the Berlin metro one last time. While we were eating, I got an email from Deutche Bahn notifying me that our train had been canceled. I could reschedule, they said. I noticed with some relief that there were other trains at about 11:00 and 13:00. The DB website directed me to select a new ticket. I tried both of these, but they were so full that they would not allow me the required seat reservation. At that point, I gave up and started looking for buses. All of the Flixbuses were booked for the day. It was a bit more expensive, but I did find two from BlaBlaBus. The problem: the next one left in 45 minutes! We dashed down toward the metro, but missed the connecting public train by 1 minute. That was probably fine in the long run, because in my haste I had somehow hit a button to navigate to the wrong station and hadn’t had time to double check it. We took a nice public transportation tour of Berlin, got to the bus an hour ahead of the 11 o’clock departure, and rested as we munched on a pastry in the bus station. Hopefully, Deutche Bahn will refund the train ticket, though that seems questionable at this point from what I can tell. One way or another, we are on a bus for Prague.