Amritsar

A Lot of Everything

From the moment we walked outside the airport in Amritsar on Thursday night, we were accosted by people trying to work us for a few rupees. As is the case in Latin America, taxi drivers swarm you at the airport exit, asking prices far above the going rate. This is especially true if you look like a foreign tourist. It was already well past dark. It was hot and humid, and I couldn’t get Uber to work, so I just went along with the cab fare. The guy was only asking for six dollars for a 10km trip, after all. Did it make that much difference that the going rate was two or three? It did matter a little. Uber leads drivers right to your desired location. With language barriers and inaccurate Google Maps locations, taxi drivers sometimes leave you to find your own way once they get you in the neighborhood. That’s what happened to us.

I had been told by many people not to book motels online in India. “You need to see the room yourself,” they told me. I looked up a place online that seemed to meet minimum standards at an attractive price, and had the cabbie take me to (within a couple of blocks of) it. It had air conditioning, WiFi, and seemed clean enough. One disadvantage of doing it this way is that you don’t automatically get the posted price. I was getting worked again. I negotiated the price almost back down to the advertised rate. It was late, and again, we were talking about nickles and dimes.

This scenario played itself out time and again throughout India. I really got tired of being worked. Time and again on reflection, though, I felt a little ashamed for being disturbed by it. Everything is so cheap in India, and people are so poor, was I really haggling over 20 or 50 or 100 rupees? One hundred rupees translates to $1.20. The advertised rate for my room was $11/night. A meal went for about $3 in a restaurant and much less if you bought street food. I guess I got ripped off a few times, but it was for smaller amounts than I lost when my pants went through the laundry or what fell into the car seats. Buying a single 20 oz drink from a convenience store rather than a box store in the U.S. incurs a bigger penalty.

Poverty in India is real. Neighborhoods all over the country have random hanging tied together electric wires strewn about haphazardly. I nearly walked into a nest of about three dozen twisted wires with their exposed junctions as I stepped out of that first taxi in Amritsar. Skinny, undersized children with matted hair countless times came up to me in the street begging for 10 rupees… 10 rupees. Twelve cents. One poor fellow begging in the Amritsar train station when we left had one foot sticking about six inches out of the bottom of his torso, and was swinging himself around on that and his hand on the opposite side. As difficult as his life would be in the best of locations, imagine going through life with this disability in Amritsar, India. Rain washes who knows what down the streets. Piles of trash sit up and down nearly every street with dogs and cows and flies working them over. Once we saw a cow stretching her tongue out an incredible distance to lick some garbage that was sitting on top of a cement pedestal away from the birds who were eating it, right there on the side of a major street. There are streets even built over the tops of other streets in many places, dripping gunk occasionally on careless pedestrians below. Some ground level streets are big enough for cars, others only rickshaws, and a few are too small for rickshaws. Some rickshaws are motorized, others must be pedaled. Some poor fellow will peddle you a few kilometers for what amounts to a quarter.

In 2022, India surpassed China to become the most populous nation on the planet. It is a chaotic place. There are people everywhere. Most are going somewhere, many others are trying to take you somewhere, still others are trying to sell you something, and a pretty significant remainder are just laying there. We saw people sleeping on the street, on benches, on ledges, in the train station, and just about everywhere. Lines are non-existent. When you are waiting to get in somewhere, it’s every man for himself. People are constantly pressing against you, pushing past you, cutting in front of you, hitting you with their packs or bags if they have them. Most people just pack what they have in plastic sacks. The streets are jammed with cars, rickshaws, carts, wheelbarrow-like things, and people walking. Once during our visit, we got caught in a traffic snarl so bad, we couldn’t even walk through it. We were afoot, and eventually gave up and took a different route.

All of this destitution, chaos, and filth at least helps me understand to some extent Rudyard Kipling’s ardent support of British colonialism. He wrote that it was the burden of Western Civilization to shepherd the underdeveloped forward; to civilize them. He complained they didn’t always appreciate it. But it seemed obvious to him that dragging people like Indians into a modern economy and infrastructure was best for them, whether they wanted it or not. At first blush, it really does look like India could use some developmental help. Why wouldn’t they want to enjoy the economic benefits of British or anyone’s presence?

We didn’t have trouble getting where we needed to go on Friday morning. Our motel was within walking distance of several of the main tourist sites in Amritsar. We went first to the Jallianwala Bagh Memorial. This site commemorates the massacre of a few hundred Indians by the British Indian army. During the first world war, the UK implemented special wartime measures involving strict rationing of supplies and tightening restrictions on citizens. Indians expected these to be dispensed with as soon as the war was over. Instead, the Rowlett Act effectively announced their permanent adoption. Although the Rowlett Act was never implemented, one can imagine the sentiment it aroused. Protests ensued and several Europeans were beaten. Four were killed. A British officer with a provisional Brigadier General rank in the Indian service (this was distinct from the British Army) by the name of Reginald Harry Dyer was placed in charge of keeping the peace in Punjab where the protests were especially rowdy.

In early April, 1919, Dyer essentially placed the area under martial law. He forbade assemblies of more than four people, had troops forcibly end protests in a few places, and dealt with Punjabis with a particularly heavy hand. This only aroused deeper discontent. On April 13th, a group of around 10,000 Indians gathered in Jallianwala Bagh – some of them for a large religious festival, others to protest, many were probably there for both. Jallianwala Bagh was a rectangular enclosed area with only one entry and exit point. Dyer posted his Indian troops at the opening and without warning ordered them to open fire on the crowd. They continued firing until their ammunition was nearly exhausted. Estimates vary as to how many were killed, but the number was in the hundreds at least. Thousands more were injured. Some were killed in the press of people trying to escape somewhere. Another 120 were killed as they jumped into a well to avoid the bullets. Dyer’s troops marched back to their post, leaving the dead to decompose in the April sun. It was an atrocity in every sense of the word. The truth needed no embellishment.

As Secretary of State for War, Winston Churchill condemned Dyer’s actions. So did the House of Commons. The House of Lords praised him for defending British India. Dyer was forced to retire, but not sentenced to any sort of criminal punishment. The memorial presentation, as might be expected, canonized those who died as martyrs for India’s statehood. And it is true that Jallianwala Bagh accelerated the growth of sentiment for full Indian independence rather than just more autonomy under British rule. But the presentation gave no thought to what could have provoked or led to the massacre, other than attributing it to pure British evil. The protesters are described as peaceful, when recent riots had already killed and injured quite a few people. Britain is portrayed as being unapologetic and completely unsympathetic. They even kick around old Rudyard Kipling, who, in all honesty had nothing to do with the incident. They attribute the House of Lords’ statement to him, claiming he called Dyer “the savior of British India.” They also accuse Kipling of leading a £2,600 fundraising effort for Dyer after he had been drummed out of the service. It was a pro-colonial newspaper that actually did this. Kipling did make a contribution, but it was a measly £10. When because of his reputation for supporting British colonialism, Kipling was asked to provide some quote to be used at Dyer’s funeral in 1927, all he contributed was a rather cautious, “He did what he thought was best.”

There was plenty of wrongdoing to point out at Jallianwala Bagh. There was no reason to bring Kipling into it, other than that he has become the academic world’s whipping boy in its postcolonialism fetish. Go ahead and kick Dyer. Kick the British Indian Army. Largely made up of Sikhs and other Punjabis, they get off without any censure in the museum presentation. Kick the House of Lords for not only defending Dyer, but lauding his actions. The procurators even punch at Churchill, one of Dyer’s strongest critics, for British Indian policy during the war.

If there is something to criticize Kipling for, it isn’t his tepid response to Jallianwala Bagh. It is his warped view of how peoples and civilizations develop. Kipling was no hater of India. He was born there, and loved it dearly. He just didn’t understand how Indians could succeed economically and developmentally in a timely manner without assistance. Was he wrong? Well, English colonialism did not turn out to be an effective remedy for India’s ailments. Why was he wrong? I really think it is just as simple as understanding that no one wants to be told what to do. Just as individuals can’t be dragged toward economic advancement against their will, so also societies must advance of their own volition to have the national pride and self worth that comes with achieved successes.

Consider Jacob Riis, the Danish activist for urban reform in the United States back around the turn of the 20th century. Immigration was booming. Immigrants packed themselves into squalid conditions in New York tenements, trying to squeeze as much money out of their earnings as they could to send home or to advance their families’ start it America. A brilliant photographer, Riis brought the living conditions many immigrants endured to the attention of Progressive Era social activists and urban reformers. Many changes were made to building codes and inspection authorities were created to enforce them. Limits were placed on how many families could be packed into an area. The problem with all of this was that there was a market for these squalid conditions, and a reason why people were willing to put up with them, at least in the short term. They were trying radically cut down their expenses, not because they liked living in squalor, but so that they could climb out of the squalor. What were the effects of Riis’s efforts? All of those changes made urban housing substantially more expensive. More tenants were hurt by the subsequent rise in housing costs than the difficult living conditions. The bottom line: government mandated advancement nearly always comes slower and with unintended side effects. When people want to improve their living conditions, they will do it on their own. You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink.

The problem with British colonialism in the late 19th century was that it was trying to force economic development on people. Very few people view anything they were forced to do as an improvement. When Indians resisted or protested, the British responded by making them do more things they didn’t want to do. Both sides doubled down on their responses until Dyer’s absurd overreaction at Jallianwala Bagh in 1919. It is probably true that Indians would never on the whole be satisfied without complete independence after such an incident. Reading the historical presentations both at Jallianwala Bagh and the Partition Museum, I was left with the impression that British colonialism left one other unfortunate scar on India – a victim’s mentality. Perhaps it was just those who have ownership of telling India’s historical tale. Maybe not everyone feels that way. Indians were victims of Dyer’s crime. It’s fair to assign blame to the British government as a whole, but the presentation extends blame to every British citizen they can name regardless of their role in – or even condemnation of – the terrible event at Jallianwala Bagh. This would be even more evident when we visited the Partition Museum.

We got our first taste of one other distinct part of our Indian experience at Jallianwala Bagh. While we were there, at least half a dozen families or groups wanted to take selfies with us. At first I thought it was just that they all thought Caleb was a cute, blondish kid. But they wanted to take photos with me, too. By the time we left India, I had taken photos with more strangers than the president. Just about anyone who spoke some English was excited to try it on us as well. Across the board, India is an extremely welcoming place. It is odd to say that about a place where you get swarmed with swindlers as soon as they see you’re a foreigner. It is even more strange to have such a warm welcome at a place where you could be mistaken as one of the perpetrators of a mass murder. There were a couple of people who looked a little askance at us, apparently not knowing we were Americans rather than Brits – I mean, we fought a war for our independence against them – but these were rare exceptions that we never once saw again after we left the Jallianwala Bagh Memorial. Even there, most people were genuinely excited to have America visitors interested in visiting and learning about their country. It was heart warming, and the most cherished memory I have of my time in India. I have never felt more welcomed.

(Continued)

After the memorial, we walked to the Golden Temple (Harmandir Salib). This is the most holy place in the Sikh religion, and home to the deified Adi Granth, the Sikh holy scripture. As religions go, Sikhism is relatively young. It was founded and developed by a series of gurus. These gurus led the religion until after about ten of them, one bestowed permanent guru-ship on the text itself. The Golden Temple thus houses the deified copy of the text. The temple and pool – which people actually use for ritual cleansing – were initially constructed in the late 16th century. The temple was damaged several times during Moghul and Afghan incursions. It was rebuilt more or less in its present form by Ranjit Singh, who gave it the gold leaf finish that inspired its name. The temple suffered more damage in 1984 when Indira Ghandi’s government attacked it in response radical Sikh activism determined to have originated here.

The Golden Temple is one of the most visited sites in Amritsar. Everyone recommends visiting at daybreak. Due to the makeup of our travel party, that wasn’t going to happen. It was midday by the time we arrived, and it was hot and humid. Admission is free, but you are asked to wear a head cover and remove and store your shoes. I noticed near the place we stowed our shoes that there was an ample supply of lightweight bright orange kerchief like head covers. This was the temple’s trademark color. All of the pike-weilding Sikh guards had turbans of this color, and the spire shaped poles were wrapped in shrouds that matched. Unfortunately, all of these free head covers appeared to have been already well used. I opted to convert my own sweat mopping handkerchief. Caleb had no alternative but to grab a musty loaner.

We made our way around the edges of the pool, stopping to look at several shrines. About half way around, we came to the langar, a free kitchen open to all castes and faiths. We were invited in and directed to sit on the floor after collecting clean metal place settings. Periodically, volunteers came by with pots and ladles. They offered us different stews and soups, some rice, and some pudding. They were all vegetarian, but the spices in the pea soup were surprisingly good. Caleb didn’t eat much, I think mainly out of trepidation.

We made our way around the rest of the quad and ended up in the line to go see the scriptures in the main central temple. The line for this was very long, unless you were a lady with children, in which case you had a separate entry with almost no wait! Since lines are meaningless in India, there is a pen about 15 feet wide in which you wait. Every several meters, one or two of the Sikh guards had a metal pole laying across the fencing that set the pen’s boundaries. A crowd of people would be allowed to advance, then the next crowd would be allowed into the previous section of pen. We had to really mind what was happening in front of us, because once the bar went up, people would just stream around and in front of you if you weren’t ready to move. Even after the guards lowered the bar, another couple dozen people limboed under. I guess they were not afraid of the pikes.

It took about about an hour of advancing through the pens to reach the temple. There were several monks chanting around a copy of the scripture on the bottom floor, and several part human, part animal idol statues around the corners. There was an even bigger copy of the text on the second floor, with only a single monk or two around it. All of the altars had a sort of slotted bin where you could place or toss donations and they would be caught in a receptacle, reminiscent of the device used to harvest pistachios. We were allowed all of the time we wanted to contemplate the images and the place. Many Sikhs were sitting Indian style on the floor in the upper level, soaking up the ambiance – the spirit and the sound – where the big text was. We were invited to join and did. We stayed longer than most tourists, though not nearly as long as many of the supplicants.

In our congregation in Luling, Texas, a thoughtful and kind attorney named Bill Watson taught the Bible Class each Sunday morning. I remember him offering an explanation for the “levels of heaven” obliquely referred to in II Corinthians 12, but embedded in people’s minds through culture, Dante’s Inferno, etc. He was clear to point out that this was his speculation rather than doctrine. He said he thought maybe people who had a more spiritual mindset in life had a better appreciation for being near to God, and thus their experience would be better, even if they went to the same place after death. It seems reasonable. Similarly, I feel like I get more out of visiting historical sites than the average tourist for having better than average knowledge of the significance of the site. I fell clearly in the opposite camp when it came to Sikh and Hindu sites. I felt my dearth of knowledge impeding my ability to fully appreciate the importance of this, the most sacred of all Sikh places. It was impressive, to be sure. Perhaps it will inspire me to learn more. After all, that’s what travel is supposed to do.

I knew one thing for sure when I left the Golden Temple. I was hot. We were planning to attend the well known “Beating Retreat” ceremony at the Attari-Wagah border with Pakistan later that evening. I decided to go to the Partition Museum. I thought it might be a good opportunity for Caleb to learn about the India-Pakistan rivalry while we rested in the air conditioning for a couple of hours. It was an interesting museum, again with a very one dimensional presentation of India’s past. Britain continued to face demands to devolve control of its imperial possessions after World War II. By this time, Britain had determined they would follow a policy of self determination. British India had once stretched from modern Pakistan to Burma. Burma had been occupied by Japan during the war, and gained its own independence in 1948. The areas that are now Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh were to be granted independence around the same time.

Under severe pressure to make this happen even more quickly, Lord Mountbatten, the last British Viceroy of India, oversaw an accelerated process that ultimately granted Indian independence at midnight August 14-15, 1947. British India contained a complex mix of people and religions. There were princely states that had some level of autonomy even during British rule, there were Muslims, Sikhs, and Buddhists, Bengalis, Punjabis, and on and on. Leaders of many of the Muslim parts of British India wanted their own state. Polls were taken in all of the areas and it was determined that British India would be partitioned to form the modern states of India and Pakistan. This seemed like a reasonable decision, but the line had to be decided upon and drawn in a matter of weeks. Even then, religious adherents did not fall neatly along one side or the other of a line, so millions of people became refugees, desperately seeking to reach the other side of the new line before or immediately after India and Pakistan became independent.

As often happens in situations where there are so many people moving for ideological reasons, there were crimes committed by hate filled people and opportunists on both sides of this divide. With all of the poverty in India, you can imagine how difficult the traveling conditions were. It is estimated that as many as 18 million people migrated, and as anywhere between 200,000 and 2 million died in the chaos, either from starvation, difficult conditions, or were killed outright by partisans.

The blame for this, as might be expected by now, was placed unilaterally on the British. So even in granting Indian independence, the British are bashed for how they did it. To be fair, partitioning the country in a matter of a few weeks caused many problems. But what was the alternative? Continue under British rule? The museum implies that all of the territory that had been British India should have been left under Indian control. This obviously disregards the wishes and interests of Muslims, Bengalis, and those who supported the formation of Pakistan. It is hard to imagine a newly devolved India absorbing all of those disparate groups against their will without even more severe problems. Yet, the British continued to try to assist in every way they could. They continued to supervise the monetary system until both countries had established control of their own currencies. Mountbatten stayed on as governor general. The bottom line is that there had been Hindu-Muslim riots going on for some time, and nothing Britain could have done would have lessened that tension, even had the British been inclined to do so. The British coffers were empty from the war. Some kind of military crackdown obviously wasn’t the answer. Not partitioning India seems destined to have set the newly independent country up for disaster. Had the partition not happened, the subsequent disaster would have also been blamed on Britain. Again they bash on Winston Churchill, Queen Elizabeth II, and just about everybody. It was an informative museum, if you read the information with the extreme postcolonial interpretation in mind. It was also one of the few places we were treated rudely our entire time in India. Maybe we looked British.

(Continued)

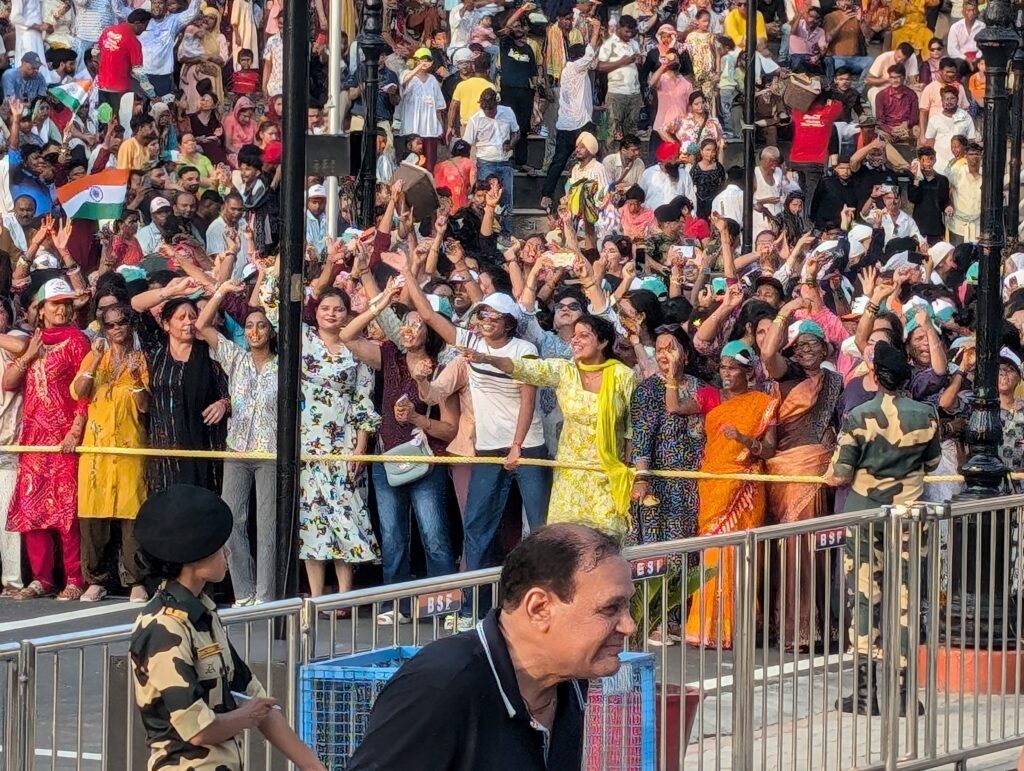

The highlight of our cultural tour of the Amritsar area was our visit to the Attari-Wagah border to observe the retreat ceremony. Retreat is a military procedure by which the flag is lowered at sunset. We took a rickshaw all the way out to the Pakistan border from our motel in old town Amritsar, a distance of about 30km. It took over an hour. Each country has built stadium seating so visitors can observe this parade of sorts that has been going on since the country was partitioned in 1947.

As foreign guests, we were offered a fast track entry into the stadium for the free ceremony, and given prime seats. We had been advised to arrive early, and so sat in the sun for a good hour or so before the festivities began. This allowed us the opportunity to be swindled one more time. A vendor made his rounds through the crowd of foreign guests with little boxes of mango juice, offering them to us feigning no knowledge of English. I initially refused, but he persisted. I asked, “How much?” He waved his hands as if it were free. This seemed plausible, as they made such an effort to make foreign visitors feel welcome at this venue. I reluctantly accepted the juice box, and allowed Caleb to do the same. Of course, a few minutes later, the guy came back to ask for money. Again, I asked him, “How much?” This time he understood perfectly well. “Ninety rupees,” he replied. I noticed a sign below that said all vendors were required to sell their wares for the same price and even listed price for the mango juice – 20 rupees. I reluctantly handed him a 100 rupee note, to which he said, “Ninety rupees each.” I suppose I could have refused this, but I just gave him another bill and took my 20 rupees in change. I had been had, again, this time for $1.70. Still, it was annoying. I hadn’t even wanted the stupid juice in the first place. I made sure he knew I was annoyed, but left it at that.

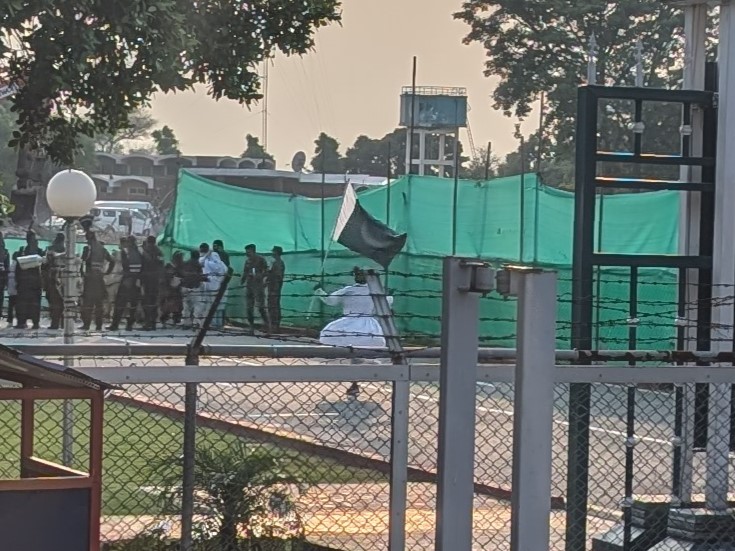

I didn’t let it ruin my day. About an hour before sunset, they started playing music and videos on the India side. Something was happening on the Pakistan side as well, but we couldn’t hear it. A huge group of dancers formed in the street below us, jumping up and down and dancing to the music, chanting and singing. I looked across to see what was happening in Pakistan. A one legged man in a white robe slowly hobbled out to the center of the street carrying a Pakistani flag. All of a sudden, he dropped his crutches, held the green flag with its crescent and star over his head and began spinning at an amazing rate, even for someone with both feet. His robes twirled out around him like a Southern debutante’s dress. This was a pretty impressive stunt. Nevertheless, the poor one-legged flag bearer seemed a little sad compared to the dancing mob of colorfully dressed ladies on the India side.

Periodically between songs, a mustachioed Indian Border Security Force officer in a beret would come out with a microphone as if he were at some World Wrestling Federation event and pump up the crowd with challenge and response chants. After a long sustained battle cry, he called out, “Hindustaaaaan…,” and the crown hollered back, “Zin-da-bad!” This means something like, “Long Live India.” Apparently, this is also chanted at India-Pakistan cricket matches. That seems entirely appropriate. The whole thing was kind of like an international pep rally. I’m pretty sure the Pakistanis were chanting something similar on the other side.

The main event featured high stepping border guards with fan shape crests on their hats marching out and ceremonially opening the gates between the two countries it what looked like some fascist dance-off. Two of them eventually met across the boundary in a very formal, stiff handshake. The two flags were lowered simultaneously, and the gates closed. The parade itself was not all that long, but with the build up, it took about an hour. It was quite the patriotic production, and nowhere were Indians more excited to see us than here, to share their love of country. Eventually the BSF insisted we and the Indian tourists taking selfies with us move along toward the gates. That’s probably a good thing, otherwise who knows how long we’d have been there. One very enthusiastic little stocky fellow was especially excited to see Caleb’s enthusiasm about the ceremony, and kept hollering at him, “Hindustaaaaan….” futilely trying to get him to correctly pronounce “Zindabad!” in response. Both he and Caleb had fun with the effort. I got a kick out of it, too. “Hindustan, Zindabad!”

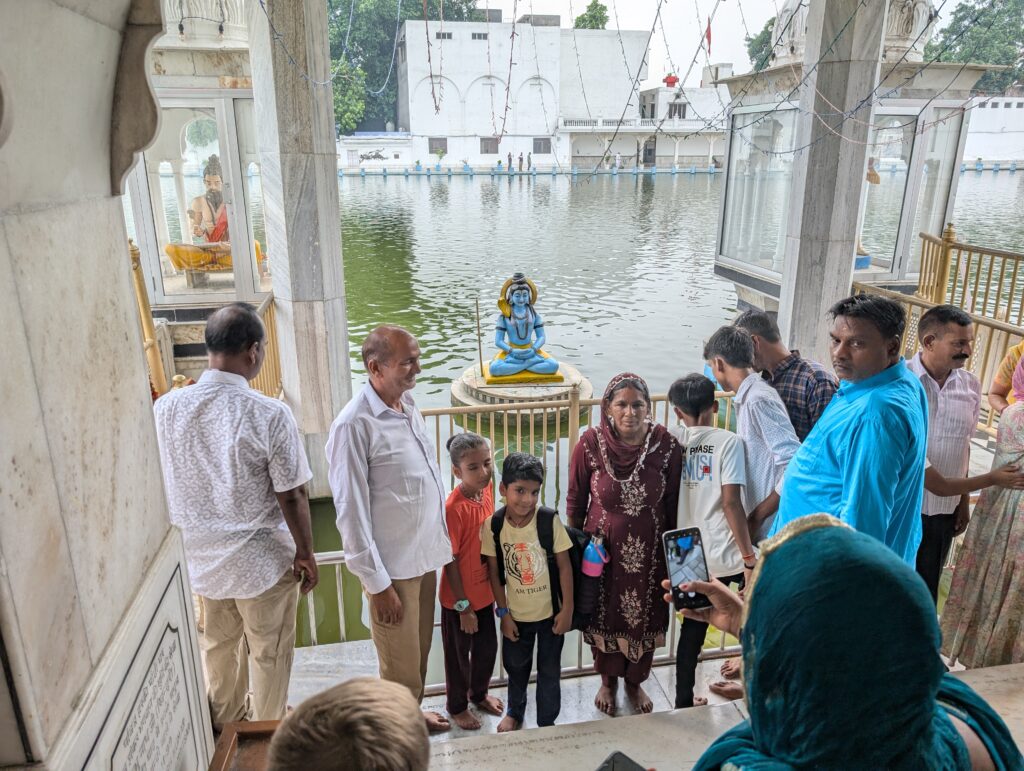

The next morning, after I waited for Caleb to sleep in, we walked to the Durgiana Temple. This is a Hindu temple dedicated to the goddess Durga. Durga is associated with protection, strength, motherhood, destruction, and wars. The original temple was built during the 16th century, but this iteration dates to 1921. The design and architecture were heavily influenced by the nearby Golden Temple. It was a bit earlier in the morning, and there were very few tourists at Durgiana, making our visit more pleasant. We accidentally entered through a side gate where we were again asked to deposit our shoes, but this time no head covering was necessary. We walked the inner perimeter of the pool, looking at the peripheral shrines and alters. There was also a tree where some of the more important founding events in Hinduism were supposed to have occurred. Considering the temple’s importance in Hinduism, I was a little surprised how few people were there. We made our way quickly into the main temple in the center of the pool without having to wait through the pressing crowded pseudo-line. In neither temple are you allowed to photograph the inner shrines, but we were able to observe the statues, which again I probably would have appreciated more with a deeper understanding of Hinduism.

Caleb had had his fill of temples and really wanted to see Gobindgarh Fort, so that’s where we went next. The fort had been constructed centuries ago by clans, but was captured and greatly improved by Majaraja Ranjit Singh. Singh survived small pox as a child, but lost an eye to the disease. He ruled the Sikh empire in Punjab in the early 19th century. He sought to improve the Sikh army by infusing European tactics. As such, he employed European and American veterans to train and help lead his troops. The British used the fort during their colonial period, and remained in use by the Indian Army until 2017 when it was converted into a museum/theme park. As theme parks go, it is pretty small. There are a few kiddie rides and you can ride a camel. Caleb rode the camel.

The fort spans over 43 acres and boasts massive walls and moats. It is not entirely clear from the museum displays what of this was built by Singh and what was built by the British. We enjoyed wandering the grounds and ramparts. There was a small cultural dance in the main square, and an armament museum. We enjoyed looking at a small numismatic museum as well, though this was an additional charge and had almost all replica coins.

Caleb made a friend here. There was a 21 year old Sikh student from Delhi visiting Amritsar on his own, sightseeing. He befriended Caleb and they chatted and argued (in friendly tones) about this and that throughout our visit, which lasted most of the middle part of the day. We enjoyed some street food in the square, a fried mixture of potatoes and some kind of peppers.

Our task in the afternoon was to have our laundry done. I learned that to my surprise, no one in Amritsar would do laundry and return it the same evening. Further, there were no laundromats. We were about out of clothes, so we ended up just hauling our dirty clothes on our train ride to Agra after church. We sent out our clothes once we got to Agra, but they did not smell all that clean when they returned, and we were charged something like 50 rupees per item, which adds up pretty quickly on socks and underwear. We had been encouraged by the motel owners in Agra to hand wash them. For the rest of the trip, that’s what we did. This was much easier than I thought it might be, the results were far better, and I never lost control of my clothes. For someone my size, the latter would have been a significant travel disaster. So, for 10 rupees worth of detergent and a few minutes work once a week, our laundry dilemma was permanently solved.

We had two tasks on Sunday. We planned to attend worship in Amritsar, and we needed to catch the train to Agra at 4:00 p.m. The Church of Christ in Amritsar meets in the home of a kind brother who works in a textile plant in the city and does the preaching there. Amritsar is a city of 1.5 million people, and this house church is the only Church of Christ congregation there. At about quarter to 11 Saturday evening, I was asked to preach the next day. I was a little surprised by this, but I have a repertoire of sermons I have preached several times. I do rely on notes, though, which I did not bring. Stephanie was kind enough to find a few examples of relatively simple messages. I was able to pull those up and refer to them on my laptop as I was preaching. Brother Noble, who preaches in a town 150 kilometers away took a train all the way to Amritsar to translate. I had plenty of time between translations to refer to my notes.

I am pretty sure Brother Mangal purchased this home with the intent of hosting worship. He had a large open air outer room covered with carpets for people to sit on. There were a few chairs for ladies and the elderly, but most of us sat on the floor. Just as in the temples, we took off our shoes when entering. There was no air conditioning, so it got pretty warm. The locals seemed used to it. People continued to roll in as the service went along. By the latter part of worship, there were about 50 people in attendance. I am not certain how much of the sermon came across due to language and cultural barriers, but people were genuinely welcoming and excited and encouraged to see us. We were so happy to have a place to join our brothers and sister for worship. After services were over, we enjoyed a delicious chicken biriani plate.

Throughout the morning and early afternoon, we were repeatedly encouraged to retreat into Brother Mangal’s bedroom, which had a room air conditioner. I often look like I am not handling the heat well. I sweat like a horse, which actually helps, but it makes me look pathetic when in hot climates or eating spicy foods. For most of the time, I declined. I wanted to mingle and visit as long as others were staying. I figured if they could deal with it permanently, I could deal with it for a couple of hours. As people began to leave, we eventually gave in and cooled down for an hour or so before heading down to the train station.