Azerbaijan

A Cult of Personality

Like Georgia, Azerbaijan is a former Soviet Republic – a place that would have been difficult if not impossible for me to visit earlier in my lifetime. It is another country in the Caucasus that wants to be part of Europe, but has much in common with Asia; a place along the old land trade routes between Europe and the Far East. Much of Azerbaijan looks geographically like it could be part of the American Southwest. Riding across the country to visit the 18th century Sheki kahn summer palace, it looked in many places like we might have been driving along Interstate 40 someplace in Arizona or New Mexico. Azerbaijan is oil and gas rich, like Texas. Vast stretches are dotted with pump jacks like the Permian Basin. Stretches of the interior had been leveled and canal irrigated at some point, but that enterprise had apparently been deemed not economically viable as most of the dry, salty land had been abandoned to salt brush like parts of the Southern San Joaquin Valley along Interstate 5 out near Buttonwillow. Dry ridges crop up here and there, looking like California’s coast range, or a desert hog back somewhere near Mojave, minus only the Joshua Trees.

Like Georgia, Azerbaijan has some fascination with pseudo sci-fi modern architecture. There are a lot of strangely shaped buildings, though at least some of them – like the flame towers – do at least seem to have some reason for looking the way they do. Baku’s flame towers are shaped like tongues of fire. They display a light show every night that rotates between fiery images reminiscent of the energy industry that powers the country’s economy and patriotic images of a soldier waving the Azerbaijan flag, or the flag simply fluttering in the breeze.

Azerbaijan does have its Caucasus high country, but it is either drier than Georgia’s mountains, or we did not see its highest, greenest parts. Unlike Georgia, however, Azerbaijanis seem to have embraced tourism. The scenery may be a little less picturesque, but there are some interesting historical sites and it is nice to feel as if people want you in the country for something other than to squeeze a few lari or manat out of you.

We met more than one local interested in sharing the history and identity of their country. Those we met were all quite patriotic. The country is run by what is essentially a family dictatorship, established by Heydar Aliyev and continued by his son, the current president of Azerbaijan. I never met one Azerbaijani who had anything negative to say about him. Unlike the feeling you get in Turkey that perhaps there is not a single person in the country who believes Erdogan has any redeeming qualities, the Azerbaijanis we met seemed to put Heydar Aliyev on a pedestal, often referring to him as “the father of our country.” His son seems to be just a few steps behind.

In semi-Soviet fashion, you see Aliyev family propaganda everywhere. Although there are not Mao style building sized murals to the late leader, there are highway bill boards all over the country with his official portrait superimposed over the national flag. Several of the museums and historical sites we visited had placards and explanatory signs infused with praise to Heydar Aliyev or the Aliyev family for valuing, sponsoring, or somehow making possible the carpet museum, the restoration of a historical site, or the preservation of some critical component of Azerbaijani heritage. The most interesting part of all of this to me was that it was harmonious. It didn’t feel as if there was some massive state campaign to convince people to love someone they found objectionable.

Another interesting Soviet era hold over not as evident in Georgia was the presence of state manufactured cars. The Soviet Union of course created state manufactured cars during its tenure, which ended in 1991. Apparently some of these cars were built after the collapse of the Soviet Union. You see these cars still running now and then in Georgia and in the city of Baku, but once you venture out into the countryside, a large minority of the cars are these cookie cutter, non air conditioned old cars. Some have been converted to have AC, and many are in remarkably good condition. They are apparently inexpensive and easy to work on. Soviet military equipment in World War II had the reputation of being inexpensive and mass produced, but not of the highest quality. These cars must not have been complete junk, or there wouldn’t be so many of them still on the road.

I often heard one other peculiarly dissonant note while traveling Azerbaijan. Azerbaijanis are essentially cousins to the Turks. In many places you see crossed Azerbaijani and Turkish flags. The language is really a dialect of Turkish. It uses similar letters and pronunciations. Both Turkey and Azerbaijan are Sunni dominated secular Islamic countries. The political ties between the two are all the closer for the support Turkey has given to Azerbaijan in her post-Soviet clashes with Armenia. Armenia and Georgia are historically Christian. Since all three of the Caucasus countries were recently part of the Soviet Union, they have not always established and maintained their own borders. The demise of the Soviet Union bequeathed independence on Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, but also left them with the responsibility of working their differences out amongst themselves. Armenia and Azerbaijan have fought border wars at least twice since the collapse of communism. To this day, it is nearly impossible to enter Azerbaijan if you have a recent Armenian stamp in your passport. All around Azerbaijan, you see patriotic memorial displays honoring Azerbaijanis who gave their lives in the conflicts with Armenia, due to “Armenian aggression and attacks.”

Students of history will note that the Turks attempted to exterminate Armenians during the first world war. Many Armenians fled to the San Joaquin Valley of California as a result of what is fairly called “the Armenian Genocide” perpetrated by the Ottomans in 1915 during the waning days of their empire. Although I never saw a reference to the Armenian genocide anywhere in Azerbaijan, several times I read displays talking about how Armenians had perpetrated genocide on Azerbaijan. One very sincere tour guide explained to us that modern Armenians only claimed to have an ancient history and heritage. “Just like there is a Balkan Albania and a Caucasian Albania that have nothing to do with one another, modern Armenia has no relation to the historical Christian kingdom of Armenia. The Soviet Union began moving (modern) Armenians in to the area in about 1978. Before that, no one spoke Armenian. But people revived the old language and now you have these people here today in our land.” If you think this sounds eerily similar to the Arab explanation of the modern state of Israel, and their casus belli for constant attacks on that country, you are not alone.

I suppose all of this goes to show that many of the world’s most problematic conflicts have long histories. Most people look to history only to support their own existing interpretation of present events rather than seeking to understand the tenacious roots of modern conflicts. Both sides will always have a relatively recent grievance to avenge, so there is always ample fuel to keep the fires of hatred burning. I am not saying these deep seated ethnic and religious struggles don’t often have a “more guilty party.” I point out only that they are nearly always complicated feuds that predate contemporary issues or the memories of current participants or observers. The conflicts become embedded in the identities of the cultures who are involved to the point that not hating a traditional enemy can make people feel unpatriotic or less Azerbaijani, or Armenian, or Israeli, or Palestinian (or Soviet, or American). There is obvious danger in this kind of thinking. It certainly isn’t a world view likely to bring peace, internal or external. I do not know how to move whole cultures past carrying this historical baggage. I do know that having an awareness of it is a good first step. An even more productive next step would be promoting history so that at least the false narratives are not used to further grind old axes.

(Continued)

Our first encounter with Azerbaijan came through its state run airline. When we left North America, the land border going from Georgian to Azerbaijan had remained closed since the Covid pandemic. The most recent guidance suggested that Azerbaijani government was “cleaning the border stations” and projected their opening by July 1. Until then, the e-visa policy was not very restrictive, but you had to enter the country on a flight. As a green observer, cleaning border stations seemed to me like something that could easily be accomplished between May and the beginning of July, so I went on with my plans to travel by land from Edinburgh all the way to Baku. It became apparent while we were in Georgia that the land border was not going to open anytime soon. I was baffled by this, until I was reminded by the Georgian tour guide who also explained to us why the ski lift wasn’t working that the Azerbaijani government (the Aliyevs) held a near monopoly on flights in and out of Baku. They stood to profit significantly by keeping the land border closed under the now thin guise of Covid concerns.

If we were going to Azerbaijan, it would have to be on a ridiculously short flight from Tbilisi to Baku. I buckled and bought the tickets. On the bright side, the Azerbaijan Airlines experience was a pleasant change from domestic flights in the U.S. There were a few inches between my legs and the seat in front of me – even in coach. We were served a hot meal even on a one hour flight. The boarding process was a little less than professional, but the overall comfort of the flight was a significant improvement over what I have grown used to on U.S. domestic commercial flights.

We arrived in Baku on Monday morning (at Heydar Aliyev International Airport) and hopped on an airport express bus to cover the 20km between the airport and city center. Baku has a very nice, comfortable city bus system. There is also a two line metro we really didn’t use much, as there was a bus stop near our hotel. The Madinah hotel was the best accommodation value so far on the trip. We had a nice large semi-luxury room with complimentary breakfast for less than $35/night.

Since there were a few hours left in the day, Caleb and I elected to visit a couple of local sites before eating dinner and calling it a day. We decided on the fire worship sites north of town. We took the city bus system a little over an hour to the Atashgah Zoroastrian Fire Temple. Our bus route ended in the neighborhood where the temple is located, leaving us some distance to walk. Some locals had edited the location of the temple in Google Maps so that it would lead to their house instead of the nearby temple. The owner of the house then had a child not much older than a toddler walk us over to the temple entrance in exchange for whatever gratuity the travelers might offer. They did not insist or even ask for the gratuity, but it seemed obvious that was the arrangement. We gave the friendly child a couple of manats, but rolled our eyes a little bit at the scheme.

The source of Azerbaijan’s oil and gas wealth also generates surface gas emissions that, once ignited, can cause an eternal flame effect. Ancient peoples may not have understood the natural explanation of this phenomenon, but they understood it was a special and unique place. It became a holy site for Zoroastrian worshipers prevalent in this area before its Islamic conquest. Zoroastrianism is an ancient Persian religion you can read about here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zoroastrianism. The temple itself is relatively small, and there are only a few placards around describing pieces of the structure itself and a little bit about Zoroastrianism. Interestingly, the descriptions of Zoroastrianism at the two sites we visited this day differed significantly.

There are recorded mentions of Zoroastrians, Hindus, and Sikhs coming to worship fire on this Caspian Sea peninsula as far back as 1,000 years ago. The original temple seems to have been destroyed by Muslims, who also ran the Zoroastrians and Indian religious practitioners off to India. Indian merchants remained active in trade in this region, however, and pilgrims from the religions mentioned above made treks here to visit the eternal flame, and the one at Yanar Dag. Much of the present temple complex seems to have been constructed in the 17th and 18th centuries. The eternal flame went out in 1969, due to either oil and gas extraction or an earthquake, depending on who you ask. The fire in the temple is now fueled by piped in gas. It was kind of a cool site, and an inspiration to read a bit more about Zoroastrianism. Even I, as a pokey visitor, did not need more than an hour to feel like I had thoroughly seen it.

The guide with another group of tourists invited us to catch a free ride with them to the other fire site, Yanar Dag. A twenty minute ride with them seemed more attractive than a public transpo ride an hour longer, so we hopped in. Yanar Dag is another site that was somehow ignited long ago and burns continuously due to gas emissions. It really is just the side of a mountain with a little vertical spot of about 15-20 square feet that looks like the dirt is on fire. Well, there is a fire, it just doesn’t consume anything. There is an amphitheater where you can sit and watch it burn, with a few buildings containing some explanatory placards behind. It is on the Baku tourist trail, so a lot of people come see it, I guess out of obligation.

We got more out of the personal interaction than the visit. The tour guide who picked us up had introduced himself as Russell, but his name was really Ruzi. He told us he got called “Rosie” so often by English speakers that he just started introducing himself as “Russell.” He was a friendly fellow and spoke very good English himself. Ruzi’s English was entirely self-taught. He had taught himself a few other languages as well. Much of his language had been acquired via movies, as he could quote more English language films than we could. Ruzi told us a lot of positive things about Azerbaijan, the Aliyevs, and the area in general. He had invited us along mainly in hopes of selling us a different tour on a later date. The hospitality was genuine, though, and he was a pleasant guide. I ended up booking a tour with his company on Wednesday. They gave us a ride all the way back to town that evening, where we grabbed a couple of shawarmas and hit the sack with plans to visit the museums and historical parts of town on Tuesday.

I was able to run each morning in Baku whereupon I explored the town a bit more. The city has an impressive sea-front promenade and a beautiful skyline with modern buildings, a crescent shaped hotel and a “Baku Eye” modeled obviously after the one in London. Once Caleb woke, we enjoyed our complimentary breakfast overlooking the Caspian Sea, then walked over to the Carpet Museum – which is actually shaped like a carpet. As you might imagine, the museum is dedicated to explaining the art and process of creating the carpets that come from this area. They are an important part of Azerbaijan’s heritage. It was in interesting place to spend an hour, and the building is pretty cool. Interestingly, pro-Aliyev commentary is infused throughout the literature explaining about the carpets. Heydar Aliyev had apparently been primarily responsible for the creation of the museum.

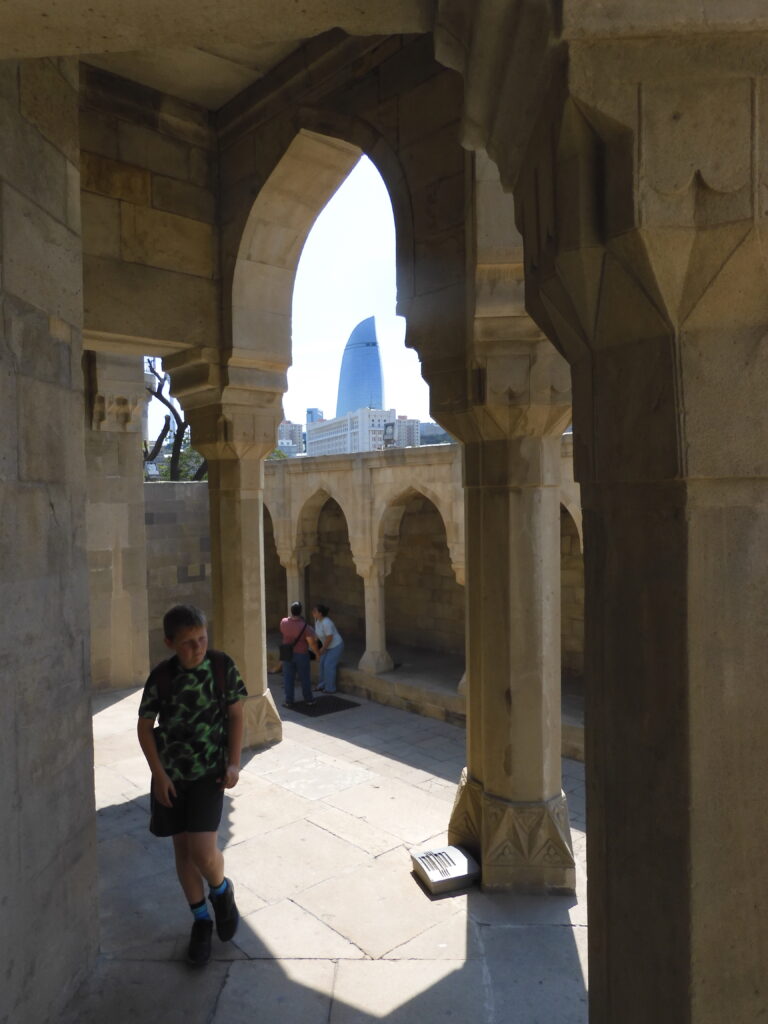

We later visited the Palace of the Shirvanshahs, old town Baku, and the Maiden Tower. These areas are all obviously old and historical, although many of the exact details of their histories have been lost over time. Baku was an important location due to its position on this peninsula jutting into the Caspian Sea, but it was not a capital until the Shirvanshahs moved their palace here following an earthquake during the 15th century. Shirvanshahs were the rulers of a region called Shirvan from the 9th century to the 16th, when they were conquered by the Safavid Empire (Persians after they had become Shia Muslims). Exact dates are only known for things like the Safavid conquest that are mentioned in external sources.

There are really no artifacts left in the Palace of the Shirvanshahs. Mostly, you visit to see the building itself and learn about the medieval state of Shirvan and its rulers and people. They do have several 19th century cultural artifacts here and there in the building, but they seem anachronistic considering the age of the building. It is an impressive palace, though. It creates a bit of a problem for interpreters. How do you explain the history of an obviously historical building that you don’t know the history of? This presented a problem at the Maiden Tower as well. I suppose this does not create a problem for many tourists, as most visitors seem intent on walking the area and snapping some photos without reading the signage even at places that are thoroughly and accurately interpreted. In the end, it is a fun and interesting stop that leaves you with a sense of mystery, and allows your imagination to wander a bit about what it may have been like here in the age of caravans and fire worshiping pilgrims.

Baku’s old town is a commercialized tourist mecca full of shops and restaurants surrounded by a well preserved city wall. It is a fun place to visit, and we ate a nice supper there after we were finished visiting, though we did not buy any kitsch. I had dolma for supper, which is meat filled grape leaves. This was very good. Caleb had some form of kebab, which he also liked. We walked the area en route to the Maiden Tower, which we climbed after paying our fee.

No one really knows the exact purpose of the Maiden Tower. It is a 12th century tower about 100’ high and offers pretty views of the city and surrounding areas from the observation platform on top. It could have been defensive, or it could have been some kind of temple, no one really knows. Stairs spiraling up the perimeter walls guide you up about nine floors offering resting points that have been converted into a museum of sorts, chronicling the basic history of Baku and Shirvan. Like the palace, though, the tower has few artifacts predating the 19th century. The two upper floors have holographic displays depicting items they believe were connected to medieval Shirvan, and lamenting their extraction to museums around the world. Almost none of the holographic images were functioning, so we could not even see the images of the “stolen” artifacts. I was left with a sense that if they couldn’t even keep their displays lighted, perhaps the more valuable objects were better left under the protection of the British Museum, the Louvre, and the Metropolitan Museum of New York, after all.

(Continued)

On our last day in Azerbaijan, we took a guided tour to Sheki. We don’t normally take guided tours, but I wanted to see the Sheki Khan palace, and it was a five hour drive. The buses that went that direction would never have gotten there and back the same day, and I only had one day. Guided tours did offer day trips there, and Ruzi’s company offered one. That was the only way to get there and back, so I took it. We traversed a lot of territory that as I said resembled the American Southwest. We had pleasant company on our tour, albeit with a different guide. We met Mohammad and his wife from Pakistan, who gave us all the inside scoop we will need to visit that country someday in the future. He is the CFO of a Honda plant in Karachi, and she just received her license as an MD.

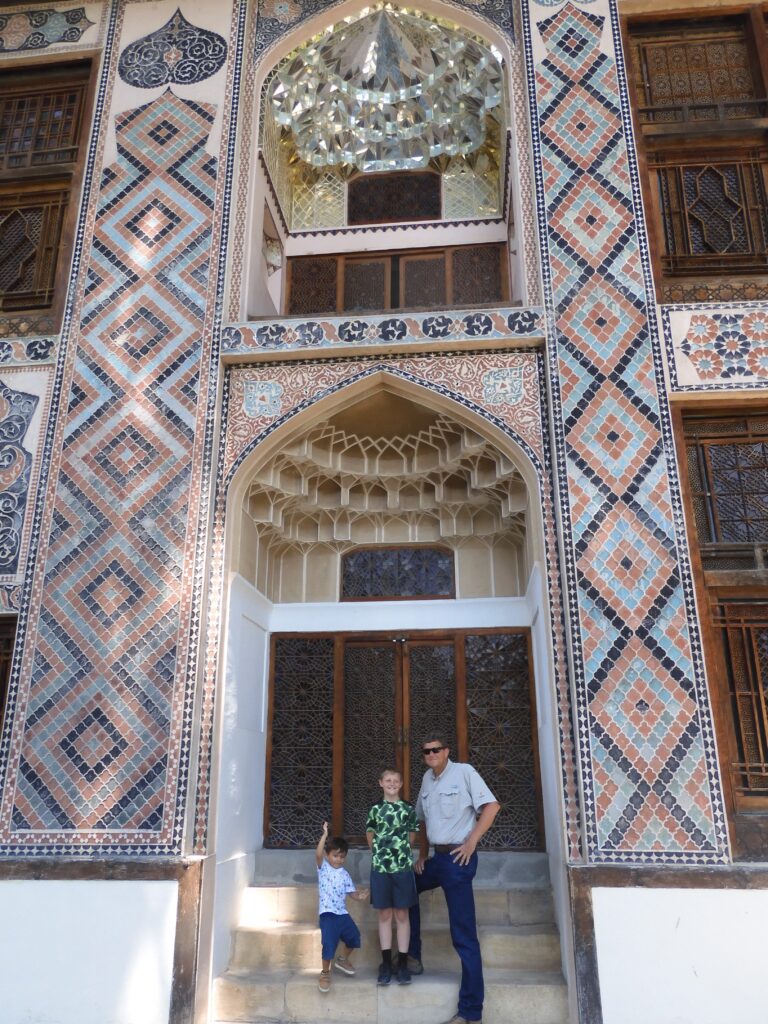

The Sheki Khan palace was an impressive, beautiful 18th century building with ducting technology to keep it cool and hand assembled stained glass windows. Everything was assembled with pegs. There are no nails. You cannot take pictures inside, which is unfortunate, since the stained glass is brilliant when caught by the sun, but does not even look colored from the outside. As with the Palace of the Shirvanshahs, there are relatively few ancient artifacts. Most of the good things were lost or plundered long ago. It is not an extremely large building, so it does not take a very long time to see. That was good, because we had a couple of other stops to visit on this trip and a long drive back to Baku.

After the Palace of the Shirvanshahs, we visited the Sheki caravanserai. This was where traders on the old silk and spice road would stop to ply their wares as they came through town. The rectangular two story structure was arranged to allow traders to set up shop on the ground level or rest in apartments above. There was a basement level for storage of goods, feed, and that sort of thing. A caravan coming through town was not an everyday occurrence, thus there was a dedicated space in the square for dancing girls, partying, and carousing. I learned also that excess livestock was also stored here. Traders bought was was effectively horse and camel insurance. Then, if they arrived with a sick, lame, or dead animal, they could trade it out as they passed. The insurance peddlers then could attempt to nurse the afflicted animal back to health and trade it off to subsequent caravans. I had no idea such an arrangement existed, and found this both amusing and practical.

We stopped for an outdoor lunch before we left town. This took longer than it should have, which put is a bit behind schedule. Our meal was tasty, though. Caleb ordered a brazed lamb dish, and I ordered a stewed lamb dish. When our plates arrived, they had identical lamb shanks laying in buttery garlic and coriander sauce. I had a lamb soup as well, which as far as I could tell had one small bite of lamb in it. All of these tasted good, though, and we were enjoying visiting with our Pakistani friends. We had nothing to complain about.

We had one last stop scheduled – an Albanian church. This area was called Albania, although it has no relation to the modern nation of Albania, which sits across the Adriatic Sea from Italy. According to legend, Christianity was spread to this area by Bartholomew who was martyred near Baku in the 70s AD. I am not an expert on Christianity’s spread to this area, but this sounds a little bit dubious to me. It is certain, though, that there were churches here in the fourth century. The conquest of Islam a few centuries later impeded the continued existence of these congregations, but the buildings remained.

Our driver intended to take us to an off-the-beaten-path Albanian church, but got lost trying to find it. We could hear him speaking to the guide and several people on the phone in excited Azeri. Our little Mercedes diesel van scrambling up rock paths all the while. After driving about an hour into the mountains away from Sheki, we seemed to reverse course. No explanation was ever made about this, and both driver and guide pretended we were just going to the intended church all along. But about an hour later, we rolled back into Sheki, and stopped at an Albanian church right there in town, not 10 minutes from where we had eaten lunch!

There are several Albanian churches in the area. They are all ancient, and they seem to all look similar, so this one was as good as any. It just cost us a couple of hours of travel time. This site had been used as a place of worship for a long time. Excavations had been made revealing stone walls from before the time of Christ, and a Norwegian researcher carbon dated cultic objects he claims were from 3,000 B.C. The current building, though, functioned most recently as a Georgian Orthodox Church, and was built in the 11th or 12th century. It was probably used as a Chalcedon Church or an Armenian or Albanian Apostolic Church in its more distant past. There are several artifacts on display, not just from the Christian history of the building, but also cultural items unearthed in the Norwegian research. Caleb was most impressed by the glass covered holes you could peer through to see human remains in the crypt.

We stayed only about 15 minutes at the church. The building was tiny, and this was enough. Searching for it, however, had put us a couple of hours behind. We had been scheduled to arrive back in Baku by 10p.m. Our driver made up some time coming back toward town, but it was after midnight before Caleb and I rolled into our hotel room to pack things up and prepare for our relatively early flight to Dubai the next morning. Other than having a bit of a short sleep night, everything worked out fine. We saved an hour of sleep time by ordering a Bolt to the airport in the morning rather than waiting on the public bus. I considered this money well spent. By midday Thursday, we walked off another comfortable Azerbaijan Airline flight and into Dubai.