Normandy

D-Day 80th Anniversary

We took a BlaBlaBus from London to Calais, where I had reserved a car. I was not exactly sure how I would get from wherever the bus dropped us of in Calais to the Avis location. Avis didn’t close until 5:30, and we were scheduled to arrive at about 4:30. Calais isn’t all that big. I figured as long as everything went according to plan, I would just Uber over or something. Our scheduled departure was then delayed by 10 minutes. The window got slightly smaller. I attempted to find an earlier bus, but ours was the only one going that direction on Saturday. I later learned that Ubers were not generally available in Calais. Our bus arrived at the ferry terminal in Dover well ahead of schedule and it seemed there would be no danger of missing the connection. We pulled into the ferry loading line a solid hour ahead of schedule, but were then told we could not board the ferry for 45 minutes.

By the time the ferry got underway, it was clear I would be left with only about half an hour to get from wherever the bus dropped us off – which still wasn’t completely clear to me – to the Avis office. I thought to myself, “I’ll just call Avis. If they know I am coming, but my ferry was delayed, surely they’ll wait for me.”

“We close at 5:30,” was the only response I got from the French Avis attendant when I called to warn them of how close it would be.

“Do you have any recommendations on how I can get there most quickly, then?” I asked. The attendant did offer the numbers of a couple of local taxi drivers.

I attempted to get off the ferry with the foot traffic so I could arrange a taxi more quickly, but was denied. Fortunately, we were toward the front of the ferry and were thus able to disembark rapidly. Our drop off point was just outside the gate at the terminal. The last taxi I had a number for was available, and he hauled us over to the Avis office in short order. We made it at 5:21. This was more fortunate than I think anyone in my party understood. I had no contingency plan. Had we missed this connection, we would have had to either wait in Calais until Monday to pick up our car or just eat the car rental and find some other way down to Courseulles-sur-mer, the site of our AirBnB. I suppose it would have only been an expensive miss, rather than a dangerous one. But it would have been a very expensive miss.

As it was, we made picked up our car on time, and set off on the three and a half hour drive to Courseulles-sur-mer. We had our first French meal en route, and arrived just after 10:00. I ordered what looked like on the menu to be a bacon and mushroom pie. It was more like a crepe with those ingredients. It was tasty, but a little different than I had expected. We had the luxury in Courseulles of a one bedroom apartment. The kids had to set up and take down a futon every day, but we adults had our own room and bed, which was excellent. Other than a slightly smoky smell seeping in from the neighbors from time to time, this was an excellent place to stay. Others have mentioned this, but I am surprised at how prevalent smoking remains in Europe. For some reason, this strikes me as especially odd, considering the emphasis on healthy foods and green transportation. It seems to fly in the face of these other ideals.

I was up pretty late Saturday night and did not exercise Sunday morning. We failed to find a Church of Christ within three hours, and so opted to hold a private family service. After this, I took a long walk down Juno Beach. The family joined me for the first couple of miles, then returned to the room while I continued. I hiked over eight miles in total, clear down to the next village and back. Juno was one of five landing beaches that were part of the June 6 D-Day assault. Americans landed at Omaha and Utah Beaches, the Brits landed at Sword and Gold Beach, and Canadians landed at Juno where they faced stiff resistance.

I have been asked by many people if French people are rude. That’s an unfortunate question, because there are kind and rude people in every culture and place. We occasionally experienced behavior most Americans would consider rude. French tourists have literally rested their arms and cameras on Kimberly’s and Stephanie heads a couple of times. This was made odious – literally – by body odor we Americans just aren’t used to emanating from armpits shoved right in their faces. People cut you off, walk in front of you, sneer when you don’t speak French, and things like that. Most of those behaviors can be chalked up to cultural differences and lack of self-awareness – a problem just as often exhibited by traveling Americans.

Any and all of these behaviors, in my opinion, were more than compensated for in the outpouring of gratitude heaped upon the allied liberators of France. We stayed at Courseulles-sur-mer during the week the 80th Anniversary of D-Day was celebrated. The village we stayed at was on Juno Beach, the Canadian landing site. There are Canadian flags and buntings on nearly every house and store. Maple leaves are painted on store windows. Wartime American vehicles roamed all along the Normandy coast. There are multitudes more French re-enactors dressed up as British, Canadian, and especially American servicemen than you would find at all American Civil War battlefields combined. There were banners hanging from every lamp post with a picture of an individual liberating serviceman, showing that some young man’s personal sacrifice helped to free France from fascist domination. There are display boards explaining one private or corporal’s personal experience on the French coast in 1944. It is a touching display of gratitude that I find far more impactful than some modern snub of an ice cream eating tourist.

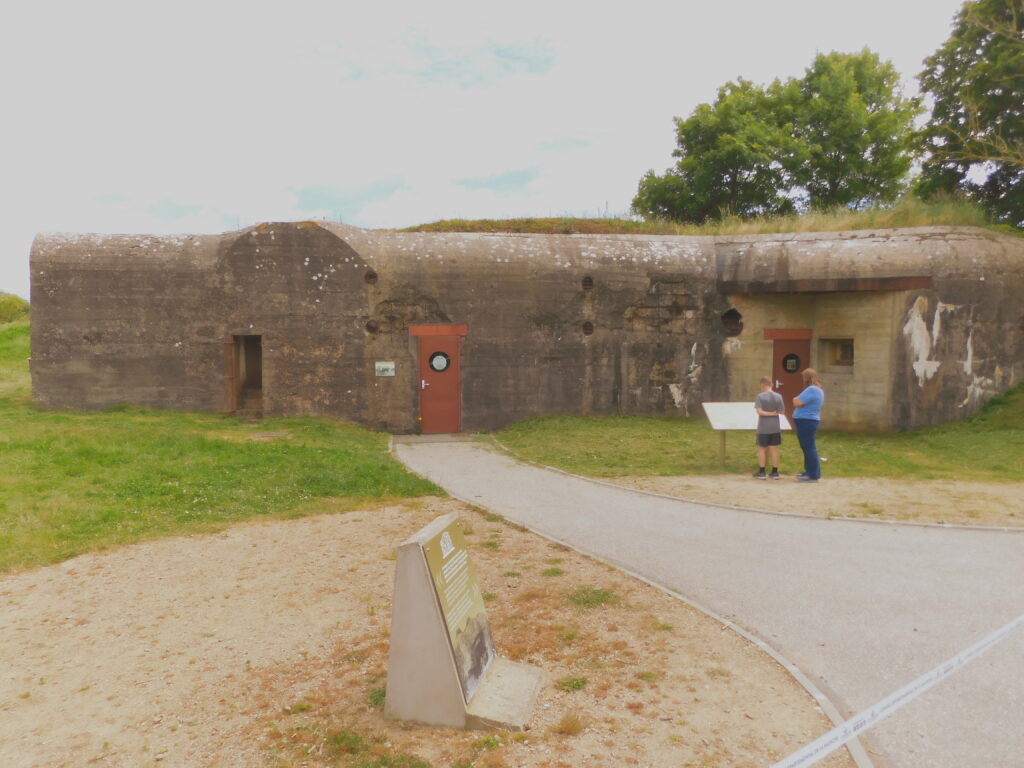

The Canadians, for their part, encountered stiff resistance taking Juno Beach. They suffered casualties surpassed only by the Americans landing on the cliffs at Omaha Beach. We of course have met a few Canadians here visiting Juno, but most of the tourists are French. As I walked the coastline, I came across Widerstandsnests every so often. These were cement bunker strongholds and gun positions posted every few hundred yards along the Atlantic Wall. They were all given numbers. Many of these are in various states of ruin and marked by graffiti. A few hundred yards inland, there are often more complex positions with more guns, tunnels, and command posts. I did not encounter these on my walk, but did run across some of the graffitied Widerstandsnests.

As I made my way back down the beach toward our room, I passed more traditional beach goers. I passed a couple of fellows with something that looked like a cross between a parachute and a kite pulling vehicles like tricycles with fat tires down the beach. The beach here runs east and west, and the wind was out of the north. The parachute-cyclists were able to keep their chutes far enough downwind to turn 180 degrees and run in both directions under wind power. Later, a group of shallow water, amphibious sail boats came by. They, too, were able to operate in both directions utilizing the north wind to run both east and west.

It took three hours to walk that far, so that it was nearing supper time when I got back – American supper time, anyway. We learned a quick lesson in cultural time. As we began to look for restaurants in which to eat supper, it quickly became apparent that most of them didn’t even open until 7:00. We found one open at 6:30 and headed that way to catch them right as they opened. We got some help and suggestions when ordering and had a good meal. Our meals came with desserts. Stephanie went the safe route and got an apple rhubarb crumble. One option was to get Normandy cheeses. I like to experiment with local cuisine, so I tried the Normandy cheese. The first one was a delicious soft, sweet cheese that I savored. I offered some to Stephanie. She preferred her ice cream. I was less enthusiastic about my second cheese. I offered Stephanie a bite of this one as well. She accurately described this second Norman cheese as tasting “like feet.” I don’t know how she knows what feet taste like, but the comparison seemed reasonably accurate. (Continued)

Stephanie shut the window blackers Sunday night, and I was up late trying to argue with the USAA customer service folks about why my Visa kept getting blocked. I woke up, and it was almost nine! Since I did not run Sunday, I was going to run Monday no matter what. I ran down Juno Beach again for a 5k, and improved my “50s” personal best. Then we headed out to look at sites around Omaha Beach. This area was completely packed with reenactors, tourists, and 40s era vehicles. Throughout the day, groups of military planes from different eras flow formations overhead. I saw more American C-130s than anything else. Most were modern aircraft, but I did spot one two-ship of Spitfires.

We went to a couple of sites protected by German firing batteries and bunkers. We then headed to the Overlord museum. The museum had a brief overview of the war, but its highlight was a huge military vehicle collection. They had many Axis and Allied wheeled and tracked vehicles. They had Panzers, Shermans, and Tiger tanks. They had an amphibious landing craft, as well as the highly effective, but extremely low-tech Higgins boat. Andrew Jackson Higgins was born in Columbus, Nebraska, but lived much of his life in Louisiana. On the Louisiana bayous, he had learned the craft of making shallow bottom boats for use in the bayous. During the Pacific Island Hopping campaign, and during amphibious landings in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, and Normandy, the army needed a specialized craft that could carry personnel and equipment right up to the water’s edge, then throw down a side to rush the beach. Higgins designed just such a craft based on his bayou experience. His company won the contract, and Higgins boats were widely used and highly effective throughout the war in American landing operations.

We left the car parked at the museum and hiked to the American cemetery at Omaha Beach. Much of this area was already off limits due to the Biden visit scheduled for the 6th. We were able to make our way back to the flag overlooking the over nine thousand white burial markers. As we walked toward the flag pole, I was deeply moved by the multitude of crosses. Most represented the life of a child about the age of one of my older sons, Preston and Andrew, cut down before even really reaching adulthood. These kids had no dog in this fight. Some were conscripts, but many volunteered. When people learn that I am a veteran, they often thank me for my service to our country. I try not to downplay the respect they are offering, but I never gave up or went through anything like the veterans who walked this field. Tears streamed down my face as I felt the sacrifices of so many young men who gave the last full measure of devotion to liberate a foreign land from an aggressive regime. I often wonder if today’s Americans would be up to a test of this magnitude, and pray that we never have to find out.

While we were waiting for the retreat ceremony that takes place each evening at 5:00, a group approached wheeling two centenarian veterans. They both spoke briefly and told us of their roles in the war. I had the chance to personally thank them for their service. I was glad the kids got to see them. Kimberly and Caleb knew my Grandpa Press, who was a World War II veteran, but I think it was good for them to meet some veterans in the context of the Normandy beaches and the 80th Anniversary of D-Day.

Our day culminated with a walk along the beach near the central monument at Omaha Beach. Access was difficult due to the areas cordoned off in anticipation of the Biden visit, but we saw the monument and were able to walk the beaches where a major part of the landings happened. For me, this was a bucket list stop. I am glad my wife and children were willing to add Omaha Beach to our itinerary.

Near the beach, we stopped at a smaller, diner like place for supper. I had some small lamb chops. We all got huge desserts with special ice cream afterward. This is why I still exercise, even when on vacation. I was up a bit earlier on Tuesday the 4th. I ran the other direction down Juno Beach and logged a total of 5.6 miles for my longest run in decades. (Continued)

Our first stop on the 4th was not a World War II site. Since we were near the town of Bayeux, I wanted to see the famous tapestry housed there. If you haven’t hear of it, don’t feel bad. No one else in my family knew what it was, either. It really is an unbelievably amazing artifact. The Bayeux tapestry is an 80 yard long 11th century tapestry. It was thought to be commissioned by Bishop Odo, the half-brother of William the Conqueror, to commemorate William’s conquest of England and to explain the chronology and importance of the Battle of Hastings fought in 1066. Prior to the Norman conquest of England, England was primarily comprised of smaller kingdoms such as Wessex, Northumbria, Kent, etc. These Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were constantly trying to fight off the Vikings, who occupied parts of the island for the previous several centuries. The Anglo-Saxons were just about to unite England when William the Bastard, Duke of Normandy came across the English Channel, defeated the Saxon forces, and created a united nation-state of England. He was the first of the rulers who predated the Plantagenet dynasty (Richard the Lionheart, Edward Longshanks, etc.). It was a huge event in the history of the Western world. Amazingly, this nearly 1000 year old tapestry survived until the present age to tell the Norman version of the story.

Of course, it is medieval art. It is two dimensional and sometimes cartoonish. But the detail included in the positioning of the horses, the faces and statures of the characters, and the hair blowing in the wind convey a surprising amount of detail. This tapestry was created to tell a story a mostly illiterate audience. It was displayed two weeks a year in Bayeux as a testimony to the righteousness of William’s cause, and the power of his monarchy. The tapestry also features friezes above and below the main illustrations, which add to the story. Unfortunately, you can’t take any pictures of the tapestry itself. They do sell postcards and replicas, so we will show some of those.

For the rest of the day, we went back into D-Day mode. We drove to the far (west) side of the Utah Beach area, and then worked our way back toward Omaha visiting sites we thought might be interesting. We visited Battery D’Azeville. This was one of the more comprehensive gun positions a few hundred yards inland, designed to provide German firing support over a wide area of coastline. There were more guns, bunkers, and trenches here than at the Widerstandsnests down on the coast. There were fewer of this type of batteries, but still too many to see them all. Several are on private property where landowners have fenced them off to charge admission. There are plenty of free ones like D’Azeville, so we stuck to those.

Back down on the beach, we found a monument dedicated to the French General LeClerc. He led a contingent of Free French units around parts of Normandy, landing on August 1, 1944. Although this had little strategic impact on the war, it was symbolically significant to the French resistance movements and the French population. When France was occupied by Germany, a collaborating French regime was put in place in Vichy, headed by French WWI hero Philippe Petain. Consider what happened to Eastern Europe and Germany at the end of the war. Germany was partitioned into zones occupied and governed by the Allies – including a French zone. Most of Eastern Europe was “liberated” by the Soviet Union and became puppet states to the Soviet regime. French participation in the allied war effort legitimized the Free French led by Charles de Gaulle as a governing body, so that no foreign military government would be put in place to control France as it was liberated. This also gave France a stronger say in what happened in Europe once the Allied victory was achieved in May, 1945. Even if LeClerc’s Free French army arrived to the D-Day party nearly two months after the British, Canadians, and Americans, their presence probably had a much bigger impact on post-war France than we know.

Walking the beach from the LeClerc monument, you can reach several more Widerstandsnests. We could also see what appeared to be oyster beds. There were quite a few tourists walking the beach in this large open area. It was spacious, and there was plenty of room to have a relaxing walk outside the bustling camps near the museums, more heavily visited monuments, and major locations where preparations were being made for visiting dignitaries who would be arriving to commemorate the 80th anniversary. It was a beautiful, cool, breezy day. I stood on the beach watching people stroll by. I felt a great dissonance. Here we were, tourists on a beautiful beach in the late Spring of 2024 – many people playing dress-up in uniforms; others just walking along eating ice cream bars along the beach; having crepes and galettes for supper in a lovely rural coastal atmosphere. How different our lives are here, now, because of what those young people from my grandparents’ generation did on this place 80 years ago.

There is a large museum and set of monuments at what serves as the main commemoration point for Utah Beach. Utah was the “other” American landing site. The Utah landing met relatively less resistance and thus made more initial progress than at Omaha. There was a huge press of people and cars parked for hundreds of yards in every direction from the museum. The monuments at the Utah site emphasize the Navy’s participation in Operations Neptune and Overlord. They mention ships participating in the bombardment of the coast, coast guard participation, a heroic group of frogmen who landed ahead of land forces in the dark of the early morning of June 6, and even the merchant marine supporters of the operation. The largest monument on the site is built into what was a Widerstandsnest. There is also a monument provided by the city of Columbus, Nebraska to Andrew Jackson Higgins, who I mentioned before as the creator of the critical flat-bottomed landing craft.

Our final stop was Pointe du Hoc, an outcropping between the Omaha and Utah landing sites. This site had what appeared to be a significant mesh of gun positions (Widerstandsnest 75) that could sweep fire on both beaches. It was thus considered critical that this position be taken out of service as soon as possible. The guns sat atop cliffs nearly 100’ high overlooking a beach only about 30’ wide. The American 2nd Ranger Battalion successfully assaulted Pointe du Hoc early in the morning of June 6th and predictably suffered heavy casualties. Of the 225 Rangers in the battalion, only 90 were able to continue the fight after the initial attack. No reinforcements were available having been put into action on Omaha Beach. The remaining 90 had to fend off a German counterattack which was not ultimately repulsed until the 8th. It was later discovered that the major guns had been removed to the further inland Maisy Battery, where they also continued to wreak havoc on the Allied attackers until the 8th of June.

The monuments and placards at Pointe du Hoc emphasize the Rangers in general, highlight their actions in this operation, and mention Lt Col James E. Rudder, who personally led his unit. There is also in interesting write up on French professional cyclist Guillaume Mercader, who played a prominent role in the French resistance. Because this site was contested for a few days and endured significant bombardment before June 6th, there are massive craters all around the gun positions, which predictably also show signs of the heavy bombardment. The point does offer sweeping views of the beaches in either direction, and was an excellent stop.

Just as we were arriving, a group of seven American World War II veterans on a visit to the site stopped to briefly discuss their wartime experiences. Because the number of surviving veterans is shrinking so rapidly – particularly those willing and healthy enough to make such a trip – the veterans they who came hadn’t necessarily fought in this particular campaign. Some were even Pacific theater veterans. Their stories were interesting, and several could speak clearly and enthusiastically about the importance of their service and the pride they took in having done so. Seeing the veterans and hearing them speak was a real capstone to our Normandy experience.

We chose to depart on the morning of the 5th, as many of the sites and even nearby roads were scheduled to be closed on June 6th. We ate “in,” in an attempt to finish off most of the food we had in the room before traveling, and prepared to head toward Paris.