Phnom Penh

Killing Fields

I made Friday, July 25th a travel day. I try not to plan any touring or other activities for travel days. The logistics of getting from one place to the next, checking out of one place and into another, and all of the intermediate travel legs – walking, city buses, ride sharing, shuttles and whatnot – occupy enough time and energy that it is best just to allow travel to have its own day.

I took a Mey Hong Company bus from Siem Reap to Phnom Pehn. My motel in Siem Reap was kind enough to arrange a rickshaw ride to the Mey Hong station, since they had stiffed me on the airport pickup that was so prominent in their advertising. The bus cost $10, and was scheduled to take six hours. I had my doubts about the schedule, which proved valid. The bus technically had air conditioning. But only a small amount of air trickled out of the vents, and that was only cool if you put your hand right up next to the vent. Your hand was then cool, until you tired of holding it up over your head. The seats were ripped, the stick-on tint was peeling from the windows, and the aroma of diesel exhaust circulated through the rear portion of the bus. After seven hours of spreading my legs while the lady in front of me reclined, I arrived in Phnom Pehn several kilometers from my motel, pasty and tired.

I was able to navigate the city bus system, which got me within a few hundred meters of my room, then walked the rest of the way to Vanny’s Peaceful Guest House, where I had reserved a room with a private bath. The air conditioner on the city bus was cranking nicely, so I cooled down some en route. My room, too, was less than what the advertising led me to expect. I was staying in a hostel. I did have my own room, which I locked by stringing a padlock through two eye bolts. My private bathroom was outside of my room, and was only private in the sense that no one else was staying on my floor to use it. The air conditioner only cooled the room down after a couple of hours. I adjusted to this by taking a cold shower each time I returned to the room and let the fan blow on my wet body until the air conditioner had had time to adjust the temperature. All of that was acceptable I suppose, considering the room cost me $12 per night. The problem is that during the off season, if you look hard enough, $12 a night can buy you a real motel room in Phnom Penh with cranking AC, a private bath, and a pool. Vanny was a kind host, though. I think I could have stayed here for less than half the price and had the same experience just by taking a hostel bed.

After cooling off, I headed out to try some Phnom Penh Khmer food from 72 Restaurant. The food in Cambodia is good and cheap. I often found cheaper restaurant food in Phnom Penh than I had in Siem Reap, probably because I didn’t venture far enough away from Siem Reap’s tourist area, and partly because it is just more of a tourist town.

I did not run on Saturday morning, knowing I had some walking to do, and I wanted to get an early start. The sites I intended to visit were related to what has come to be known as the Cambodian genocide. I would quibble with the terminology. Genocide is the systematic effort by a government or society to exterminate a particular race of people. The word has evolved in popular use to describe the worst crime you can imagine, whatever it might be often moving into the realm of the hyperbolic. No hyperbole is necessary when describing the horrors the Khmer Rouge committed in Cambodia in the late 1970s. It was one of the worst mass murders of the 20th century – a century with far too many mass murders. Shockingly, the Khmer Rouge mass murders were committed almost entirely on its own citizens. In less than four years, the regime exterminated about 1/4 to 1/3 of its own population. I struggle to call this genocide as they were killing their own people. The result was worse than many attempts at genocide.

In the wake of American involvement in Vietnam, the Cambodian government was destabilized and in 1975, a Maoist communist regime called the Khmer Rouge snatched control of the country. Their interpretation of communism envisioned an agrarian society where everyone participated in agriculture. They held all city people, the educated, business owners, banks, and anyone associated with a modern economy in suspicion or contempt. They abolished money, blew up the banks, and forced all city dwellers to move to collective farms. In a matter of a few days, Phnom Penh was almost completely evacuated. In this way, the Khmer Rouge systematically and intentionally destroyed what little there was of the fragile Cambodian economy. They demanded that rice production be tripled, regardless of environmental or weather conditions. This was impossible, of course. They exported nearly all of the rice that was produced, leading to mass famines within the country, starving or working many of their citizens to death.

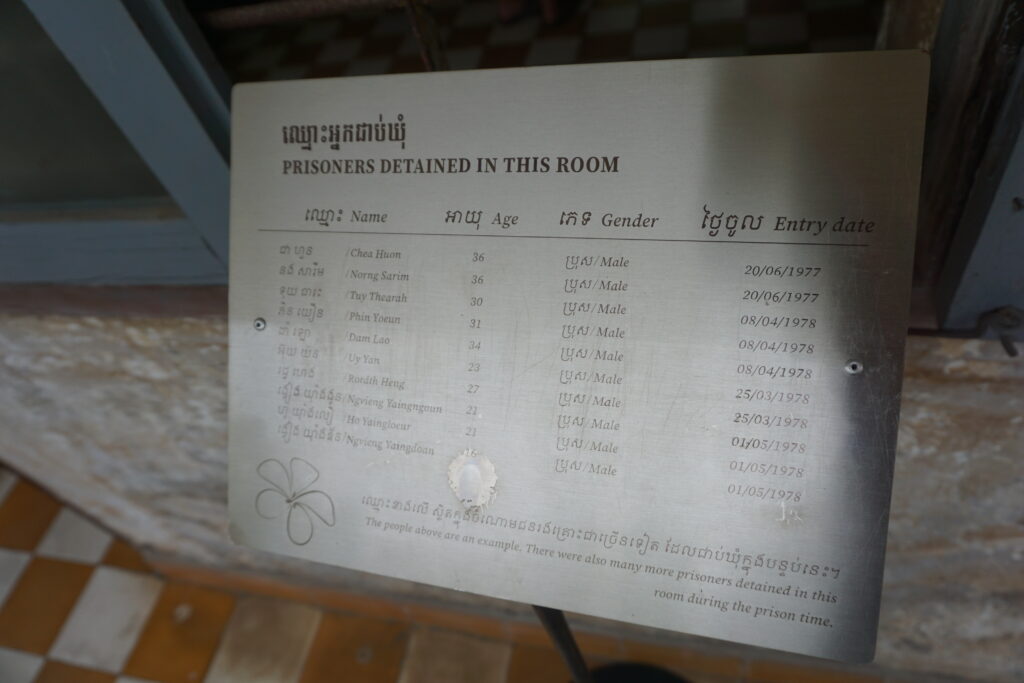

Even more deliberate and gruesome was their direct persecution of anyone with business or government experience, or an education. Anyone from a learned profession was in danger. Just having eye glasses or “soft hands” were cause enough for suspicion that you might be rounded up and imprisoned. Because the Khmer Rouge wanted to eliminate the possibility of retribution, children of those arrested and killed were rounded up alongside their parents, to suffer the same fate. People accused of acting in any way subversive to the Khmer state were likewise arrested and imprisoned. They were sent to places like S-21 also known as Tuol Sleng. They were tortured there until they produced a confession. They were then taken to places like Choeung Ek and executed without a trial. Because the Khmer Rouge did not want to waste money on bullets, prisoners were nearly always killed with farm tools, sticks, blunt objects, or other hand tools. Small children and babies were swing against a tree, crushing their skulls after which their corpses were thrown into pits. Choeug Ek is just one of over three hundred of these Khmer Rouge “killing fields” that have been discovered in Cambodia. Between the starvation and the killing fields, the Khmer Rouge killed over 1.3 million people before the regime was toppled by the communist Vietnamese government in 1979. The movie, “The Killing Fields” offers a pretty good dramatized view of the situation in Cambodia during their reign.

(Continued)

The logical visiting order for these sites would have taken me to Tuol Sleng first, then out to Choeung Ek. Since the Choeung Ek site involved an outdoor tour quite a bit further from my room, I opted to head out there first. I took a public bus to within half a mile and walked the rest of the way to the memorial site. There is a small museum there, and a large memorial Buddhist tower. Most of the buildings from the site’s service as an execution ground were cannibalized for lumber during the desperate times that followed the end of the regime. For dispatching their victims, the Khmer Rouge selected a site that had been a Chinese graveyard. A few of these older Chinese gravestones remain. The more subtle and eerie presence comes from the shallow depressions in the ground. These sunken pits are the sites of mass graves of thousands of people.

During seasons of heavy rain, bone and clothing fragments still often surface. The Buddhist caretakers of the site periodically walk the grounds and collect them. Here and there are boxes with some of these fragments. You can also see a killing tree used to dispatch babies and small children. It is decorated with memorials to the babies and toddlers murdered there. When the site was first discovered in the spring of 1979, the first people entering the camp found the tree caked with the blood, brains, and hair of those who lost their lives there.

My daughter, Audrey, often comments with revulsion at the macabre practice common in some parts of Europe and Latin America of displaying human remains. I have to say that I, too, was taken aback at seeing Francisco Pizarro’s skeleton complete with bashed skull on display in a glass box in the cathedral in Lima, Peru. Human remains are very much a part of the memorial at Choeung Ek, but it does not seem inappropriate and certainly does not come across as something to attract gawkers like the catacombs in Europe sometimes do. For one thing, ancestor veneration is deeply important to Buddhists. As such, it is not uncommon for human remains to be kept and even worshiped. That cultural aspect plays a role in how human bones are used at Choeung Ek.

Perhaps more than that, there may be no other way to show the magnitude of the brutality here than to show you the direct results. The walking tour of Choeung Ek culminates at a huge glass-walled Buddhist stupa tower filled with the bones of victims. There are seventeen platform levels of human bones. Most of what you see are skulls, because there are so many. Researches have used forensics to determine the different means of execution, and have labeled them. You can see the evidence on the skulls. They have also identified them by age, gender and identified a few foreigners. The size and number is numbing, especially when you consider that this is one of over 300 killing fields, and the giant skull stack represents only a small fraction of the people killed by the Khmer Rouge, not even accounting for the mass starvation. It feels weird and huge. Then, you look at one skull. A teenage kid. You can see how he died. You wonder what his life was like and would have been. In the course of world history what does it really matter, to lose one life? Except that it was his life. It mattered to him. He was an individual; a person you might have known or talked to. Then it really hits you. Every skull in that mountain was a person – somebody’s friend or kid or lover or frenemy or whatever. That’s when the wave of emotion overwhelms you.

As I tried to put my boots back on to leave the stupa, it came over me like a wave. I covered my face with what had been my sweat mop, and I cried aloud. Then I sobbed. Then I cried some more. It is almost beyond imagination to try to understand how and why people do the things they sometimes have done to other people. My next stop was slated to be a torture chamber that only precluded the horrors done here – where victims had no hope of escape, and where their resistance to confession to fictitious crimes only prolonged their agony.

I had originally planned to stop and eat lunch at a cooking school that takes orphans living in and around the Phnom Penh dump and gives them a usable skill. From what I understand, visitors can buy lunch there, thus supporting this useful cause. It seemed like a nice way to break up the emotional weight of an extremely heavy day. Sadly, I learned that the place was closed on Saturdays. I resorted to an old West Texas trick. In Texas, if you don’t know where you should stop and eat, it’s a good bet that whatever place has the most pickup trucks parked outside will probably have good food. I adjusted this a bit and used the ubiquitous motorbikes as my guide. I figured if all of the motorbike taxi drivers and other locals were eating at one of those open air food joints, it must be pretty good. If I was wrong, at least the food would be fresh from the high turnover rate. My guess proved right and I had a tasty, inexpensive lunch.

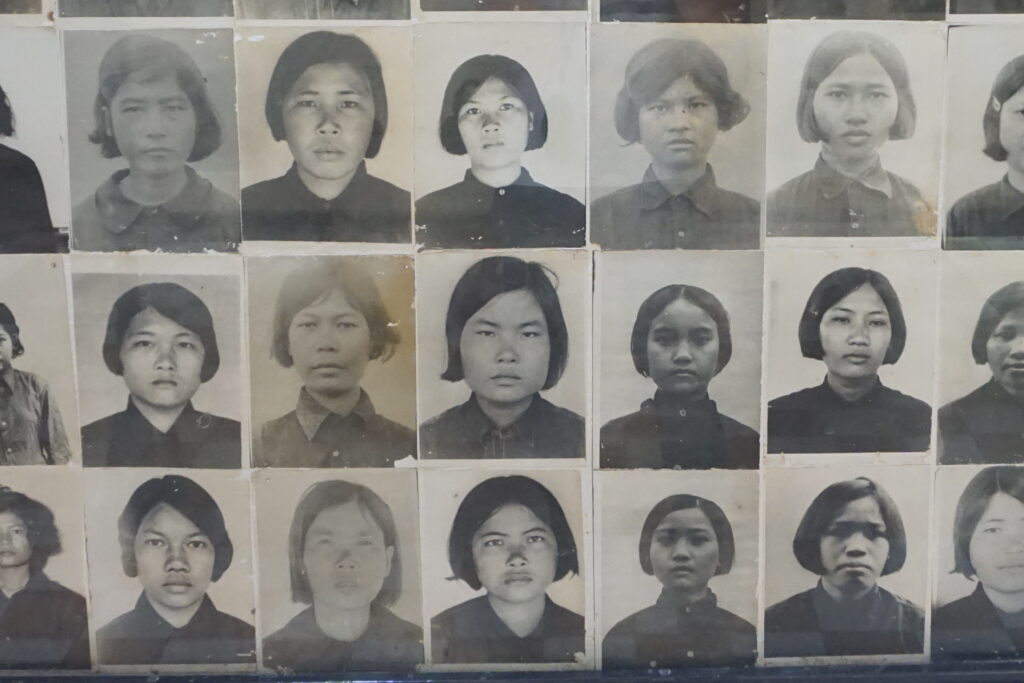

I took the city bus back to Tuol Sleng and spent the remainder of the afternoon making my way through the prison, the purpose of which I have already described. It is still a dour, somber looking place. It had been a high school before its conversion into a palace of horrors. Like many sadistic regimes, the Khmer Rouge kept good records of their own atrocities. The pictures they themselves took of prisoners who died while being tortured are on display. There are mugshots of many of the victims, though it would be impossible to display all of them. There are enough to help you understand the magnitude of the crime.

I had already seen the huge skull stack at Cheoug Ek. Perhaps the photos that most moved me at Tuol Sleng were those of the cadre. The staff doing the torturing was almost entirely made up of kids! There were some in their twenties, but more teenagers than any other age group. What must the rest of your life be like after being compelled to torture your countrymen until they confess to a crime they didn’t commit, so they can be executed? Kids were also often the executioners. If prison cadre didn’t carry out their duties, or if they made errors in their work, they were very likely to end up as prisoners in the same institution where they had just been the torturers. I hope that in that situation, I would have the courage to refuse to commit those kinds of heinous crimes. I can understand how often people did not. Who can say what any of us would do in that terrible circumstance? It seems certain, though, that survivors of the cadre would have born scars so terrible as to make the life they lived not much preferable to the death they would have been sent to had they not obeyed.

(Continued)

After a day like that, I did not want to spend the evening sitting alone in my room pondering the depths of evil that people are capable of. I decided I would go look for supper in the Russian market. I found plenty of food vendors there and ate some kind of large noodle soup with unsweetened donut sticks used to soak the soup. Cambodians eat a lot of soup. To me, that seems strange based on the inherent heat of the country. I suppose in a poor place, soups are a convenient, inexpensive, and to some extent reusable meal. Perhaps that is why they are so prevalent.

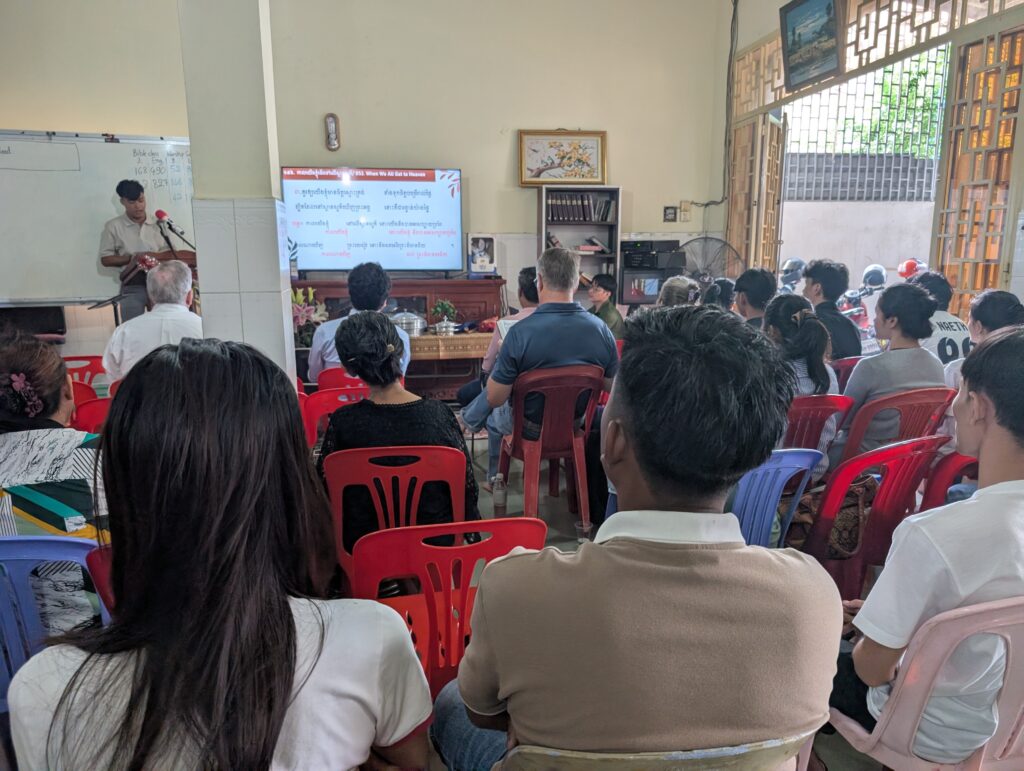

I was able to run on Sunday morning before walking to church. Friends in Thailand had put me in contact with a brother who knew of two churches in Phnom Penh. One worshiped in the morning, the other in the afternoon. I decided I would just attend both. I met some wonderful friends at the churches in Phnom Penh. They run schools there to train Khmer preachers and to teach college students the Bible alongside their other university studies. As a result, the congregations there are young, healthy, and led by locals. It is a great work that’s being done in Cambodia. The most encouraging thing is that the school and the congregations will not need outside support to continue to flourish.

I ended up spending more time talking to my fellow Texans than to the locals in the churches, most of whom speak relatively little English. I had wonderful visits, and shared most of the afternoon with them. I had my most expensive meal in Cambodia for lunch, interestingly. The Dolans sometimes crave American food and make a weekly stop at Carl’s Jr. for a hamburger. I got a Western Bacon Cheeseburger combo meal, which cost me about $9.50. I think that’s less than it would cost at home, but not by much. It’s about four times what my average Cambodian meal cost, though. Certainly, there is no substitute for the occasional reminder of a home that’s so far away.

I ate my evening meal with the afternoon congregation. I had several local treats. Afterward, I walked with the Texans to a bakery that had confections and baked goods Westerners would appreciate. I love the cuisine in Southeast Asia. I do have a sweet tooth, though. Apparently most Southeast Asians do not. Maybe this is why there are so few overweight people in this part of the world. Clearly, my hosts felt this same absence, which drew them to the bakery for cheesecakes, cookies, and that sort of thing. I did eat two cookies while there.

I had accomplished my two primary tasks in Phnom Penh already. I had seen the main sites associated with the Khmer Rouge atrocities, and I had made connections with the local church. I wasn’t really sure, then, what I would do on Monday. For not having much of a plan, I still ended up with a pretty busy day. I put my clothes in the wash, then ran my 5k, came back and hung up all the wet stuff. I took my shower, then headed out to see some sights. I went to the Independence monument. I just walked around it and took a few photos. I walked to the Wat Ounalom Monastery. The place had been built in 1447, but nothing there looked that old. The Khmer Route destroyed all of the older facilities. I tried to find a couple of restaurants, but the ones I was searching for were closed, so I just stopped in another soup stand and had some kind of minced pork noodle soup. I walked to the Coin museum, but it was closed. I accidentally found the old market, which was not closed. I walked through that for a bit. I walked the traffic circle around Wat Phnom – but just the outside. I was on temple overload by this point and had no desire to go see a modern one, regardless of showiness. I walked to the giant dome shaped new market, where I bought a 3XL Cambodian national team soccer jersey that still proved to be too small. I stopped at another stand and tried some tukatrei phaem, which was surprisingly quite tasty. After all of that, I took a badly needed shower, and made ready for a very early flight to Bangkok, where I would spend nearly 11 hours in the airport awaiting my connecting flight to Colombo, Sri Lanka.